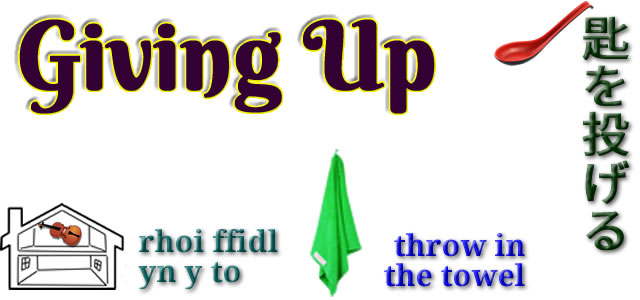

I have some news – I’ve had enough of learning languages and am giving up, throwing in the towel, putting the fiddle in the roof, throwing a spoon, and throwing the axe in the lake.

This is something I’ve been thinking about for a while. I like speaking other languages, at least sometimes, but the process of learning them can be a bit tedious. I already speak some languages reasonably well and don’t currently need to learn any more, so maybe my time would be better spent doing other things.

My other main passion is music – I like to sing, to play instruments, and to write songs and tunes. I’ll be spending more time doing this, and will maybe even focus on one instrument, at least for a while, and learn to play it better.

The question is, which instrument? I have a house full of them, including a piano, harps, guitars, ukuleles, recorders, whistles, ocarinas, harmonicas, melodicas, a mandolin, a bodhrán and a cavaquinho.

The instrument I play most often at the moment is the mandolin, so maybe I should focus on that.

If you’ve noticed the date, you may realise that this post is in fact an April Fool. I’m not giving up on learning languages, and actually do enjoy the process, most of the time, and while I do want to improve my mandolin playing, I also want to improve my playing of other instruments.

Incidentally, let’s look at some ways to say that you’re giving up.

In English you might say you quit, you’re calling it a day, you’re calling it quits you’re throwing in the towel or the sponge or the cards, or you’re throwing up your hands.

Equivalent phrases in other languages include:

- hodit flintu do žita = to throw a flint into the rye (Czech)

- jeter le manche après la cognée = to throw the handle after the axe (French)

- leggja árar í bát = to put oars in a boat (Icelandic)

- do hata a chaitheamh leis = to throw your hat in (Irish)

- gettare le armi = to throw away your weapons (Italian)

- 匙を投げる (saji o nageru) = to throw a spoon (Japanese)

- подня́ть бе́лый флаг (podnjat’ belyj flag) = to raise the white flag (Russian)

- leig an saoghal leis an t-sruth = to let the world flow (Scottish Gaelic)

- baciti pušku u šaš = to throw a gun into the sedge (Serbian)

- kasta yxan i sjön = to throw the axe into the lake (Swedish)

- rhoi’r ffidl yn y to = to put the fiddle in the roof (Welsh)

More details of these phrases can be found on Wiktionary.

Do you have any others?