When is a tomato not a tomato?

Recently I’ve been brushing up my knowledge of Mandarin Chinese by doing some Chinese lessons on Duolingo. The kind of Chinese taught there is Mandarin from Mainland China, which differs somewhat from the Mandarin of Taiwan that I’m more familiar with.

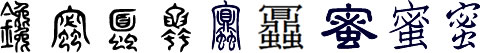

One difference is the word for tomato. In Mainland China it’s 西红柿 [西紅柿] (xīhóngshì), and in Taiwan it’s 番茄 (fānqié). 西红柿 means literally “western red persimmon”, and was borrowed into Tibetan as ཞི་ཧུང་ཧྲི (zhi hung hri) [source]. 番茄 means literally “foreign eggplant / aubergine”, and was borrowed into Zhuang as fanhgez [source].

Is 番茄 used at all in Mainland China, or in other Chinese-speaking regions?

Incidentally, the word tomato comes from Spanish tomate (tomato), from Classical Nahuatl tomatl (tomatillo), from Proto-Nahuan *tomatl (tomatillo) [source].

A tomatillo is “A plant of the nightshade family originating in Mexico, Physalis philadelphica, cultivated for its tomato-like green to green-purple fruit surrounded by a thin papery skin.” and is a diminutive of tomate – see above [source].

Other words that differ include:

| Mainland China | Taiwan |

|---|---|

| 土豆 (tǔdòu) = potato (“earth bean”) | 馬鈴薯 (mǎlíngshǔ) = potato (“horse bell potato / yam”) |

| 自行车 (zìxíngchē) = bicycle (“self go vehicle”) | 腳踏車 (jiǎotàchē) = bicycle (“pedal vehicle”) |

| 公交车 (gōngjiāochē) = bus (“public transport vehicle”) | 公共汽車 (gōnggòngqìchē) = bus (“public car”) 公車 (gōngchē) = bus |

| 出租车* (chūzūchē) = taxi (“vehicle for hire”) | 計程車 (jìchéngchē) = taxi (“vehicle caculated by mileage”) |

| 计算机** (jìsuànjī) = computer (“calculating machine”) | 電腦 (diànnǎo) = computer (“electric brain”) |

*出租車 (chūzūchē) = rental car in Taiwan.

**計算機 (jìsuànjī) = calculator in Taiwan.