A hat trick usually involves achieving three things in a row, and has little or nothing to do with hats. So where does this expression come from?

A hat trick (also written hat-trick or hattrick) can refer to

- Any magic trick performed with a hat, especially one involving pulling an object (traditionally a rabbit) out of an apparently empty hat.

- (sport) Three achievements in a single game, competition, season, etc., such as three consecutive wins, one player scoring three goals in football or ice hockey), or a player scoring three tries in rugby

- Three achievements or incidents that occur together, usually within a certain period of time. For example, selling three cars in a day

- Historically, it referred to a means of securing a seat in the (UK) House of Commons by a Member of Parliament placing their hat upon it during an absence.

The sporting senses of the expression come from cricket – in the past, a bowler who took three wickets in three consecutive balls would be presented with a commemorative hat as a prize. It was first used in this sense in 1858, when H. H. Stephenson (1833-1896) achieved such as feat in a game of cricket at Hyde Park in Sheffield. On that occasion, fans held a collection and presented Stephenson with a hat, or possibly a cap – I like to think it was a bowler hat, but haven’t been able to confirm this.

So in the magical sense, the sporting sense, and the political sense, hats were originally involved.

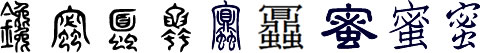

Hat trick has been borrowed into many languages. In Czech, Danish, Dutch, Faroese and Swedish it’s hattrick. In Portuguese, Romanian, Slovenian and Vietnamese it’s hat-trick, in German it’s Hattrick, in Japanese it’s ハットトリック (hatto torikku), in Korean it’s 해트트릭 (haeteuteurik), and in Greek it’s χατ τρικ (khat trik).

In Welsh, it’s hat-tric, camp lawn (in rugby and football), or trithro (in cricket). Camp means feat, exploit, accomplishment, achievement, game, sport, etc., and llawn means full, complet, whole, etc., so camp lawn could be translated literally as “a full feat”. Trithro also means three turns, three times or three occasions, and comes from tri (three) and tro (rotation, turn, lap, etc).

Are there interesting expressions in other languages with similar meanings?

Incidentally, the practise of awarding people caps for representing a team in a particular sport comes from the UK as well. In the early days of rugby and football, players on each side didn’t necessarily all wear matching shirts, and they started wearing specific caps to show which team they were on. From 1886, it was proposed that all players taking part for England in international matches would be presented with a white silk cap with red rose embroidered on the front. These were known as International Caps. This practise spread to other sports, although the caps in question are often imaginary rather than real.

Sources: https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/hat_trick#English

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hat-trick

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/H._H._Stephenson

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cap_(sport)