The Dutch word dier [diːr / diər] means animal and is cognate with the English word deer, which originally meant animal, but the meaning narrowed over time. They are also cognate with words for animal in other Germanic languages, such as Tier in German, dyr in Danish and Norwegian, dýr in Faroese and Icelandic, and djur in Swedish [source].

Dier comes from the Middle Dutch dier (animal), from the Old Dutch dier (animal), from the Proto-West Germanic *deuʀ ((wild) animal, beast), from the Proto-Germanic *deuzą ((wild) animal, beast), from the Proto-Indo-European *dʰewsóm [source], from *dʰews- (to breathe, breath, spirit, soul, creature) [source].

Some related words include:

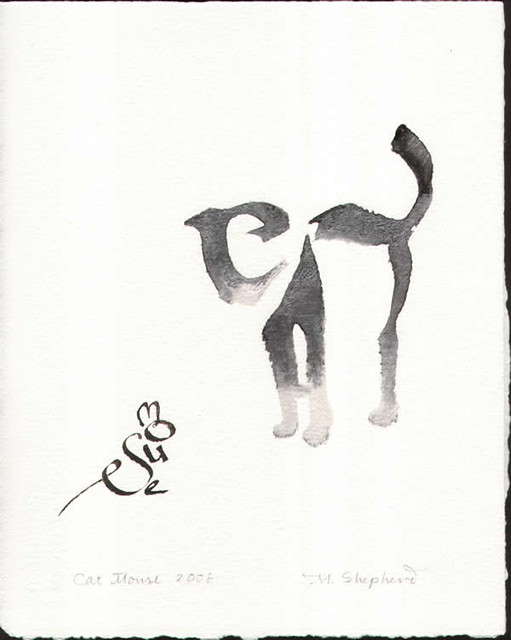

- dierdicht = poem about anthropomorphised animals

- dierenarts = vet (mainly one who treats pets)

- dierenrijk = animal kingdom

- dierentuin = zoo

- dierkunde = zoology

- dierlijk = animal, beastly, instinctive, primitive

- huisdier = pet

- landbouwhuisdier = farm animal

- zoogdier = mammal

Deer comes from the same root, via the Middle English deere, dere, der, dier, deor (small animal, deer), from the Old English dēor (animal) [source].

From the PIE root *dʰews- we also get the Russian word душа [dʊˈʂa] (soul, spirit, darling), via the Old East Slavic доуша (duša – soul), and the Proto-Slavic *duša (soul, spirit), and related words in other slavic languages.

Another Dutch word for animal is beest [beːst] which is cognate with the English word beast. Both come from the same PIE root as dier/deer (*dʰews-): beest via the Middle Dutch beeste (animal), from the Old French beste (beast, animal), from the Latin bēstia (beast) [source], and beast via the Middle English beeste, beste (animal, creature, beast, merciless person) [source].

Some related words include:

- feestbeest = party animal

- knuffelbeest = stuffed toy animal (“cuddle-beast”)

- podiumbeest = someone who enjoys being on stage and is often on stage

- wildebeest = wildebeest, gnu

The English word animal is also related to souls and spirits as it comes via Middle English and Old French, from the Latin anima (soul, spirit, life, air, breeze, breath) [source].

The Dutch word for deer is hert [ɦɛrt], which comes from the Old Dutch hirot, from the Proto-Germanic *herutaz (deer, stag), from the Proto-Indo-European *ḱerh₂- (horn). The English word hart comes from the same root via the Old English heorot (stag), and means a male deer, especially a male red deer after his fifth year [source].

Here’s an audio version of this post.