One Italian word that I learnt recently is matita, which means pencil, but looks nothing like words for pencil in other languages I know, so I wondered where it comes from.

Maita [maˈti.ta] comes from ematite (haematite), from Latin (lapis) haematites (‘haematite (stone)’, a red-coloured gem), from Ancient Greek αἱματίτης (haimatítēs – bloodlike), from αἷμα (haîma – blood, race, stock, kin) [source]. It has been borrowed into Armenian as մատիտ (matit – pencil) [source].

Words from the same roots include αίμα (aíma – blood) in Greek, words beginning with haem(o)- in English, such as haemocyte (a blood cell), haemopathy (any disorder or disease of the blood), haemorrhage (a heavy release of blood within or from the body), and emoteca (blood bank) in Italian [source].

Haematite / Hematite (Fe₂O₃) is a kind of iron oxide, is found in rocks and soils in many places. It occurs naturally in such colours as black, sliver-grey, brown, reddish-brown and red, and rods of haematite were once used as pencils. It is also used to make jewellery and other art.

Ochre, a clay containing varying amounts of haematite, which give it a red, brown, yellow or purple colour, has been used as a pigment in decoration, drawing and writing for a very long time. The earliest known examples of human use were found at the Pinnacle Point caves in South Africa, and date from about 164,000 years ago.

Incidentally, ochre comes from Old French ocre, from Latin ōchra (ochre, yellow earth), from Ancient Greek ὤχρα (ṓkhra – yellow ochre), from ὠχρός (ōkhrós pale, sallow, wan) [source].

More information about haematite and ochre:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hematite

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ochre

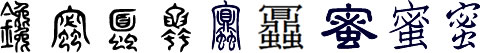

Another word for pencil in Italian is lapis, which also means sanguine (blood-red, blood-coloured), and comes from Latin lapis (haematites) ((haematite) stone), from Proto-Italic *lapets (stone). Related words in other languages include llapis (pencil) in Catalan, lapes (pencil) in Maltese, lápiz (pencil) in Spanish, and lapidary (a person who cuts and polishes, engraves, or deals in gems and precious stones), and lapis lazuli (a deep-blue stone used in jewellery [see above], and to make pigment) in English [source].

You can find out about the origins of the English word pencil in the post Pens and Pencils.