The word piecemeal means made or done in pieces or one stage at a time, but why meal? Does it have something to do with food?

Piecemeal is [ˈpiːs.miːl] comes from Middle English pēce(s)-mēle (in pieces, piece by piece, bit by bit), from pēce(s) (a fragment, bit, piece) and -mēl(e) (a derivational suffix in adverbs) [source].

Pēce(s) comes from Old French piece (piece, bit, part), from Late Latin pettia (piece, portion), from Gaulish *pettyā, from Proto-Celtic *kʷezdis (piece, portion), possibly from a non-Indo-European substrate [source].

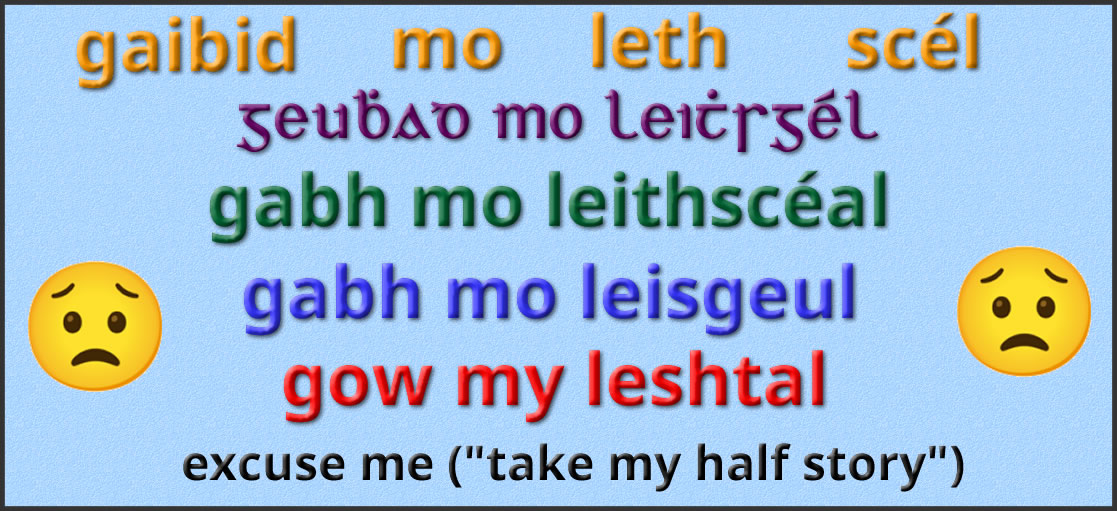

Words from the same Proto-Celtic roots include piece in English, pièce (room, patch, piece, play, document) in French, peza (piece, fragment, part) in Galician, pieze (piece, part) in Spanish, peth (thing, object, material) in Welsh, pezh (piece, bit, room, part, what) in Breton, cuid (part, share, portion, some) in Irish, and cooid (certain, some, stuff, goods, part) in Manx – for more related words in Celtic languages see the Parts and Portions post on the Celtiadur [source].

-mēle comes from Old English mǣlum (at a time), from mǣl (measure, mark, sign, time, occasion, season, the time for eating, meal[time]), from Proto-West Germanic *māl (time, occasion, mealtime), from Proto-Germanic *mēlą (time, occasion, period, meal, spot, mark, measure), from Proto-Indo-European *meh₁- (“to measure”) [source].

The English word meal can refer to food that is prepared and eaten, usually at a specific time, and usually in a comparatively large quantity (as opposed to a snack), and food served or eaten as a repast, and used to mean a time or an occasion. It retains this last meaning in the word piecemeal. Related words include footmeal (one foot at a time) and heapmeal (in large numbers, heap by heap) [source].

Related words in other languages include maal (meal, time, occurrence) in Dutch, Mal (time, occasion) and Mahl (meal) in German, mål (target, finish, goal, meal) in Swedish, and béile (meal) in Irish.

In Old English, the word styċċemǣlum was used to mean piecemeal, piece by piece, in pieces, gradually, etc. It became stichmeal in early modern English. Related words include bitmǣlum (bit by bit), dropmǣlum (drop by drop), which became dropmeal, and stæpmǣlum (step by step), which became stepmeal [source].