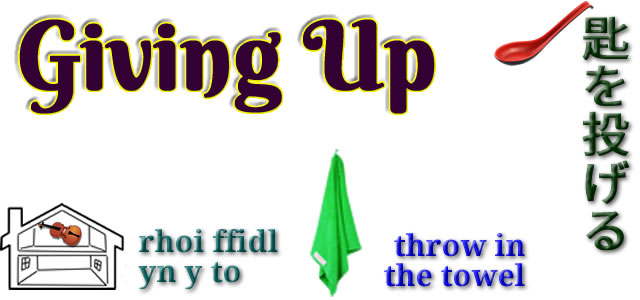

What connects the names Cathal, Ronald, Valerie and Walter? Let’s find out.

The name Cathal comes from Irish Cathal [ˈkahəlˠ], from Old Irish Cathal, from Proto-Celtic *Katuwalos from *katus (battle) and *walos (prince, chief), from Proto-Indo-European *h₂welh₁- (to rule, to be strong). The Welsh names Cadwal and Cadwaladr come from the same roots [source].

Names that also share the Proto-Celtic root *walos (prince, chief) include Conall – from *kū (dog, wolf) and *walos; Donald / Domhnall from *dubnos (world) and *walos, and (O’)Toole – from *toutā (people, tribe, tribal land) and *walos [source].

The name Ronald comes from Scottish Gaelic Raghnall [ˈrˠɤ̃ː.əl̪ˠ], from Old Norse Rǫgnvaldr, from Proto-Germanic *Raginawaldaz from *raginą (decision, advice, counsel) and *waldaz (wielder, rule), from *waldaną (to rule), possibly from Proto-Indo-European *h₂welh₁- (to rule, to be strong) [source].

Names that also share the Proto-Germanic root *waldaz (wielder, rule) include Harold – from *harjaz (army, commander, warrior) and *waldaz; Oswald – from *ansuz (deity, god) and *waldaz; Gerald – from *gaizaz (spear, pike, javelin) and *waldaz, and Walter – from *waldaz and *harjaz (army, commander, warrior) [source].

The name Valerie comes from French Valérie, from Latin Valeria, a feminine form of the Roman family name Valerius, from Latin valere (to be strong), from valeō (to be strong, to be powerful, to be healthy, to be worthy), from Proto-Italic *waleō (to be strong) from Proto-Indo-European *h₂wl̥h₁éh₁yeti, from *h₂welh₁- (to rule, to be strong) [source]. Names from the same Latin roots include Valentine, Valeria and Valencia.

Parts of all these names can be traced back to the Proto-Indo-European root *h₂welh₁- (to rule, to be strong) – the same is true for the names Arnold, Reginald, Reynold and Vlad(imir) [source].

Other words from the same PIE root include: ambivalent, cuckold, evaluation, invalid, prevalence, unwieldy, valour and value in English, gwlad (country, sovereignty) and gwaladr (ruler, sovereign) in Welsh, walten (to rule, exercise control) in German, vallita (to prevail, predominate, reign) in Finnish, vládnout (to rule, reign) in Czech, and власт (vlast – power, authority, influence, government) in Bulgarian [source].