In the UK there are many different regional words for types of bread, particularly for bread rolls, and people tend to be quite attached to their version, believing it to be the one true name for such things. Not all of them refer to exactly the same type of bread product though.

Whatever you call them, they are small, usually round loaves of bread, and were apparently invented in the south east of England in 1581 [source], although similar small loaves were probably made in other places long before that.

Here are some of the words for bread rolls used in the UK:

- Scotland: roll, bap, bun, morning roll, softie, buttery, rowie

- North East England: bun, roll, muffin, batch, breadcake, stottie, oven bottom (bread), tufty bun, scuffler

- Noth West England: barm, barm cake, bun, tea cake, muffin, nudger

- Midlands: cob, bap, roll, bun, batch

- Southern England: roll, bap, bun, cob

- Wales: roll, bap, cob, batch

- Northern Ireland: cob, roll, bun, bap

The word roll comes from the Middle English rolle (role), from the Old French rolle / role / roule (roll, scroll), from the Medieval Latin rotulus (a roll, list, catalogue, schedule, record, a paper or parchment rolled up) [source].

The word bun (a small bread roll, often sweetened or spiced), comes from the Middle English bunne (wheat cake, bun), from the Anglo-Norman bugne (bump on the head; fritter), from the Old French bugne, from Frankish *bungjo (little clump), a diminutive of *bungu (lump, clump) [source].

The origins of the word bap, as in a soft bread roll, originally from Scotland, are unknown [source].

A cob is a round, often crusty, roll or loaf of bread, especially in the Midlands of England, is of uncertain origin [source].

A barm (cake) is a small, flat, round individual loaf or roll of bread, and possibly comes from the Irish bairín breac (“speckled loaf” or barmbrack – yeasted bread with sultanas and raisins) [source]. The cake in barm cake was historically used to refer to small types of bread to distinguish them from larger loaves [source].

A batch, or bread roll, comes from the Middle English ba(c)che, from the Old English bæċ(ċ)e (baking; something baked), from the Proto-Germanic *bakiz (baking), [source].

A stottie (cake) / stotty is a round flat loaf of bread, traditionally pan-fried and popular in Tyneside in the north east of England. The word comes from stot(t) (to bounce), from the Middle Dutch stoten (to push), from the Proto-Germanic *stautaną (to push, jolt, bump) [source].

They are known as oven bottoms or oven bottom bread, as they used to be baked on the bottom of ovens, and typically eaten filled with ham, pease pudding, bacon, eggs and/or sausage. A smaller version, known as a tufty bun, can be found in bakeries in the North East of England [source]

A scuffler is a triangular bread cake originating in the Castleford region of Yorkshire, and the name is thought to come from a local dialect word [source].

A nudger is a long soft bread roll common in Liverpool [source].

A buttery is a type of bread roll from Aberdeen in Scotland, also known as a roll, rowie, rollie, cookie or Aberdeen roll [source].

A teacake is a type of round bread roll found mainly in parts of Lancashire, Yorkshire, Cumbria. Elsewhere a teacake is a light, sweet, yeast-based bun containing dried fruits, often eaten toasted [source].

In Welsh, bread rolls are known as rholyn bara, rhôl fara, rôl / rol / rowl, bab, wicsan, cwgen, cnap or cnepyn [source]. There may be other regional words as well.

Rhôl/rôl/rol were borrowed from English, and rholyn is a diminutive. Bara (bread) comes from the Proto-Celtic *bargos / *barginā (cake, bread) [source]. Cnap was borrowed from the Old Norse knappr (knob, lump) and cnepyn is a diminutive [source]. Cwgen is a diminutive of cwc, cŵc, cwg (cook), which was borrowed from English.

In Cornish, bread rolls are bara byghan (“small bread”) [source].

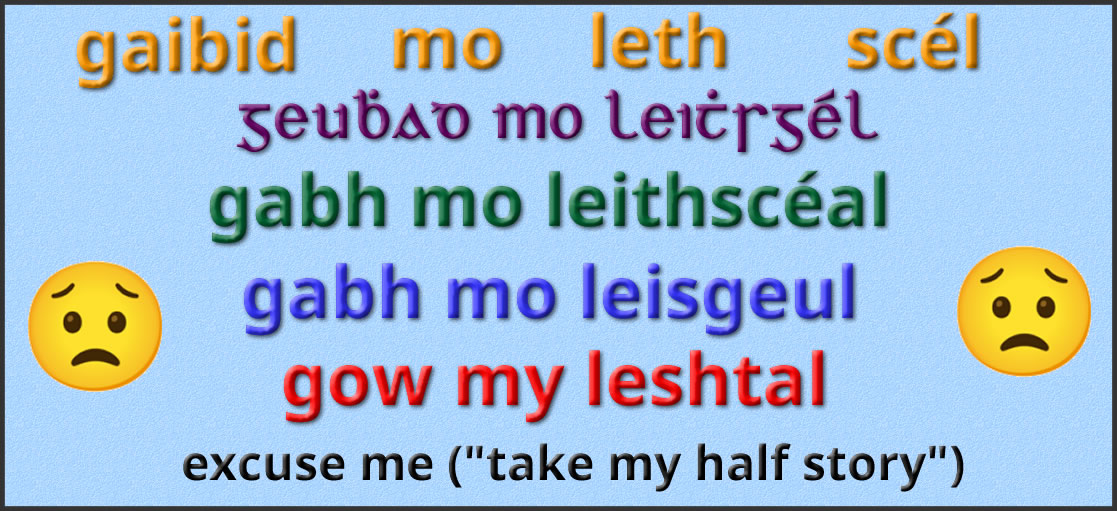

In Scottish Gaelic, a bread roll is a bonnach arain – bonnach is a bannock or (savoury) cake, and comes from the French beignet (a fritter filled with fruit), from the Frankish *bungjo (lump, bump, swelling), from the Proto-Germanic *bungô / *bunkô (lump, heap, crowd), from the Proto-Indo-European bʰenǵʰ- (thick, dense, fat) [source], which is also the root of the English words bunch and bunion.

Aran (bread, loaf, livelihood, sustenance), comes from the Old Irish arán (bread, loaf), from Proto-Celtic *ar(-akno)- (bread) [source].

See a map showing where these words are used:

http://projects.alc.manchester.ac.uk/ukdialectmaps/lexical-variation/bread/

If you’re from the UK, what do you call a bread roll?

What are such baked goods called elsewhere?