Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Here’s the latest news from the world of Omniglot.

New language pages:

- Eastern Huasteca Nahuatl, an Aztec / Nahuan language spoken in the state of Veracruz in southern Mexico.

- Ngwii (Engwíí), a Bantu language spoken in Kwilu Province in the Democratic Repubic of the Congo.

- Njebi (Yinzèbi), a Bantu language spoken in southern Gabon and the southwest of the Repubic of the Congo.

- Seki (Sekiyani), a Bantu language spoken in northwestern Equatorial Guinea and western Gabon.

New numbers pages:

- Eastern Huasteca Nahuatl, an Aztec / Nahuan language spoken in the state of Veracruz in southern Mexico.

- Njebi (Yinzèbi), a Bantu language spoken in southern Gabon and the southwest of the Repubic of the Congo.

- Northern Paiute (Numu), an Uto-Aztecan language spoken in Nevada, California, Oregon and Idaho in the USA.

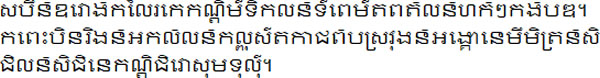

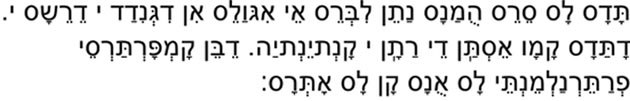

New adapted script: Nuevoladino (נוֵבָלַדִנָו / נויבולאדינו), a way to write Spanish with the Hebrew abjad developed by Murray Callahan.

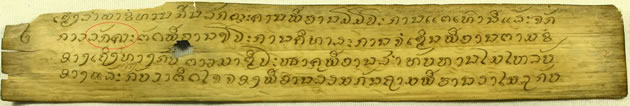

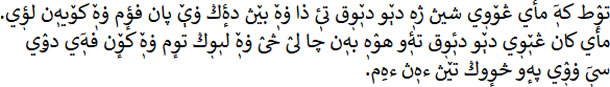

On the Omniglot blog there’s a new post entitled Calm Heat in which we uncover the hot roots of the word calm, there’s another post about the word Piecemeal, and there’s also the usual Language Quiz. See if you can guess what language this is:

Here’s a clue: this language is spoken in the northeast of India.

The mystery language in last week’s language quiz was: Huasteco (Teenek kaaw), a Mayan language spoken mainly in the states of San Luis Potosi, Veracruz and Tamaulipas in eastern Mexico.

In this week’s Celtic Pathways podcast, entitled Floors, we unearth the possible Celtic roots of words for field and related things in Galician and other languages.

It’s also available on Instagram and TikTok.

On the Celtiadur blog, there’s a new post entitled Monastic Monks about words for monk, nun, monastery and related things in Celtic languages.

For more Omniglot News, see:

https://www.omniglot.com/news/

https://www.facebook.com/groups/omniglot/

https://www.facebook.com/Omniglot-100430558332117

You can also listen to this podcast on: Apple Podcasts, Amazon Music, Stitcher, TuneIn, Podchaser, PlayerFM or podtail.

If you would like to support this podcast, you can make a donation via PayPal or Patreon, or contribute to Omniglot in other ways.

Radio Omniglot podcasts are brought to you in association with Blubrry Podcast Hosting, a great place to host your podcasts. Get your first month free with the promo code omniglot.

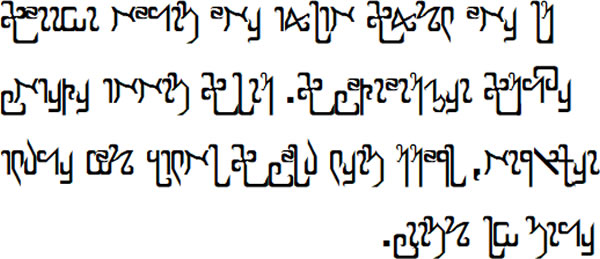

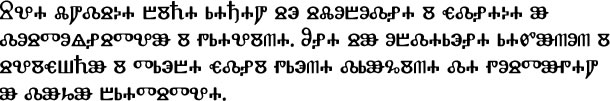

New writing system:

New writing system: