Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Celtic Pathways is a new series on Radio Omniglot that will be exploring connections between Celtic languages, and looking for Celtic roots in other languages.

The Six Celtic languages currently spoken are all members of the insular branch of the Celtic language family, which is part of the Indo-European language family. They can be divided into two groups: the Goidelic or Q-Celtic languages: Irish, Manx and Scottish Gaelic, and the Brythonic or P-Celtic languages: Welsh, Cornish and Breton. They are spoken mainly in the British Isles, Ireland, and Brittany in the northwest of France. There are also Welsh speakers in Patagonia in Argentina, and Scottish Gaelic speakers in Nova Scotia in Canada.

Other Celtic languages were spoken in the past in parts of Continental Europe, particularly in what is now France, Spain, Portugual, northern Italy and across central Europe perhaps as far as Turkey. They are all extinct, although there is a little written material in some of them, such as Gaulish, Celtiberian and Leptonic.

I’ve been collecting words that are cognate (related) in some or all of the modern Celtic languages since 2009 and putting them together in the Celtic cognates section of Omniglot. In 2018 I started exploring these words in more depth on the Celtiadur blog. I look for related words in the modern Celtic languages, in earlier versions of the Celtic languages, such as Middle Welsh and Old Irish, and in their extinct and reconstructed relatives, right back to Proto-Celtic. I also look for words from the same roots in other languages, such as English, French and Spanish.

Words of Celtic origin in other languages

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lists_of_English_words_of_Celtic_origin

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_French_words_of_Gaulish_origin

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Galician_words_of_Celtic_origin

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Spanish_words_of_Celtic_origin

https://www.uni-trier.de/en/forschung/zat/celtic-studies/celtic-cultures/celtic-words

By the way, I speak Welsh and Irish more or less fluently, can get by in Scottish Gaelic and Manx, and have a smattering of Breton and Cornish. I’ve been interested in Welsh for a long time as I have Welsh roots on my mother’s side, although she didn’t speak it. I got into Irish and Scottish Gaelic through a love of tradition music and songs from Ireland and Scotland, and I learnt the others out of interest. While doing an MA in Linguistics at Bangor University, I wrote a dissertation on the Death and Revival of Manx. Find out more in my Language Learning Adventures.

Let’s start this first episode of Celtic Pathways by looking at words for language and tongue.

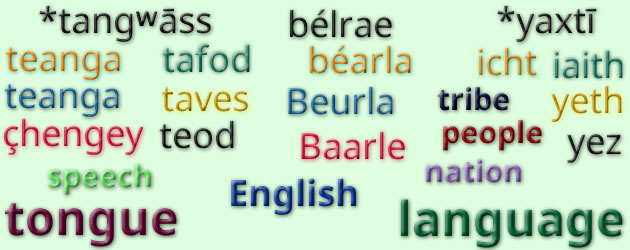

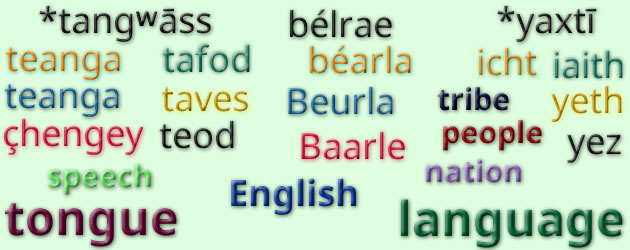

The Proto-Celtic word for language was *yaxtī, which comes from the Proto-Indo-European *yek- (to utter) [source].

Descendents in the modern Celtic languages include:

- iaith [jai̯θ] = language, tongue; people, nation, race, tribe in Welsh

- yeth [eːθ / jeːθ] = tongue, language in Cornish

- yezh [ˈjeːs] = language in Breton

The Middle Irish word icht (race, people, tribe; province, district) possibly comes from the same Proto-Celtic root.

Words from the same PIE root include: joke and Yule in English, jul (Yule, Christmas) in Danish and Norwegian, juego (play, game, sport) in Spanish, and joc (game, play, dance) in Romanian [source].

The Proto-Celtic word for tongue was *tangʷāss, tangʷāt, from the Proto-Indo-European *dn̥ǵʰwéh₂s (tongue). Descendents in the modern Celtic langauges include:

- teanga [ˈtʲaŋə / ˈtʲaŋɡə] = tongue, language in Irish

- teanga [tʲɛŋgə] = tongue speech, spit (of land) in Scottish Gaelic

- çhengey [ˈtʃɛnʲə] = bell-clapper, clasp, feather, strap-hinge; catch (of buckle); tongue; language, speech; utterance in Manx

- tafod [ˈtavɔd / ˈtaːvɔd] = tongue, faculty of speech, power of expression; language, speech, dialect, accent in Welsh

- taves = language, tongue in Cornish

- teod [ˈtɛwt] = language, tongue in Breton

Words from the same PIE root include: tongue and language in English, lingua (tongue, language) in Italian, язик [jɐˈzɪk] (tongue) in Ukrainian, and jazyk (tongue, language) in Czech and Slovak [source].

An Old Irish word for language and speech was bélrae [ˈbʲeːl͈re], from the Old Irish bél (mouth). This became Béarla [ˈbʲeːɾˠl̪ˠə] in modern Irish, Beurla [bjɤːr̪ˠl̪ˠə] in Scottish Gaelic and Baarle [bɛːᵈl], all of which mean English (language) [source].

More details about these words on the Celtiadur.

I also write about words, etymology and other language-related topics on the Omniglot Blog.

You can also listen to this podcast on: Apple Podcasts, Amazon Music, Stitcher, TuneIn, Podchaser, PlayerFM or podtail.

If you would like to support this podcast, you can make a donation via PayPal or Patreon, or contribute to Omniglot in other ways.