There’s a joke / meme that goes something like No matter how kind you are … German children are Kinder.

This is a bilingual pun – in German Kinder means children, while in English kinder means nicer, more gentle, generous, affectionate, etc. These two words look alike, but are they related? Let’s find out.

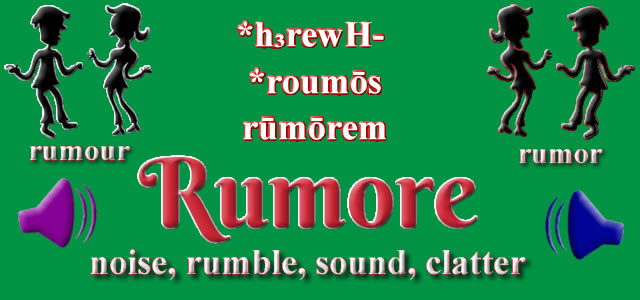

The German word Kind (child, kid, offspring) comes from Middle-High German kint (child), from Old High German kind (child, descendants), from Proto-West-Germanic *kind (child), from Proto-Germanic *kindą, *kinþą (child), from Pre-Germanic *ǵénh₁tom, from Proto-Indo-European *ǵenh₁- (to produce, beget, give birth) [source].

Kind in English means such things as having a benevolent, courteous, friendly, generous, gentle, liberal, sympathetic or warm-hearted nature or disposition; affectionate, favourable, mild, gentle or forgiving. It can also mean a type, category (What kind of nonsense is this?); goods or services used as payment (They paid me in kind), or a makeshift or otherwise atypical specimen (The box served as a kind of table).

Kind as in benevolent comes from Middle English kinde, kunde, kende (kind, type, sort), while kind as in type comes from Middle English cunde (kind, nature, sort) / kynde (one’s inherent nature; character, natural disposition), and both come from Old English cynd (sort, kind, type, gender, generation, race) / ġecynd (nature, kind, class), from Proto-West-Germanic *kundi / *gakundiz, from Proto-Germanic *kinþiz (kind, race), from Proto-Indo-European *ǵénh₁tis (birth, production), from *ǵenh₁- (to produce, beget, give birth) [source].

So, the German Kind and the English kind do ultimately come from the same roots. Are German Kinder kinder though, or are they the Wurst, and somewhat gross?

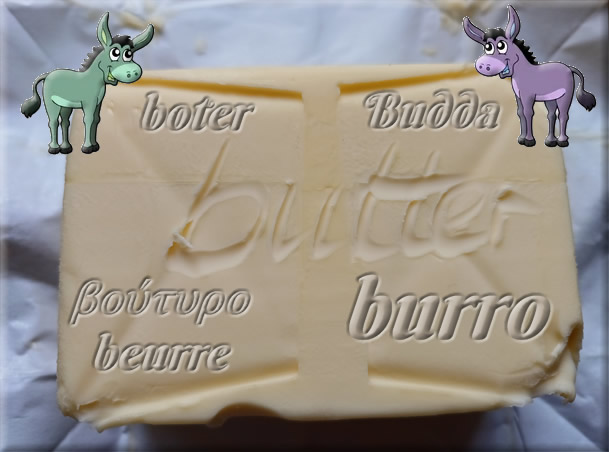

Other words produced, beget and given birth to by the Proto-Indo-European root *ǵenh₁- include: kind (child), koning (king, monarch) and kunne (gender, sex) in Dutch, cognate, engine(er), gender, gene, general, genesis, genetic, genial, genius, gentle, kin, king, nature, oxygen and progeny in English, König (king) in German, nascere (to be born, bud, sprout) in Italian, gentis (tribe, genus, family, kin) in Lithuanian, geni (to be born, birth) in Welsh [source].

Incidentally, the English word child is not related to the German word Kind. It comes from Middle English child (baby, infant, toddler, child, offspring), from Old English ċild (child, baby), from Proto-West Germanic *kilþ, *kelþ, from Proto-Germanic *kelþaz (womb; fetus), from Proto-Indo-European *ǵelt- (womb), or from Proto-Indo-European *gel- (to ball up, amass). It is related to kuld (brood, litter) in Danish, and kelta (lap) in Icelandic though, and possibly kalt (cold, chilly, calm) and kühl (cool, calm, restrained) in German [source].