A hangnail is an angry nail, not a nail that’s hanging off. Let’s find out more.

A hangnail is:

- A loose, narrow strip of nail tissue protruding from the side edge and anchored near the base of a fingernail or toenail.

- A pointed upper corner of the toenail (often created by improperly trimming by rounding the corner) that, as the nail grows, presses into the flesh or protrudes so that it may catch (“hang”) on stockings or shoes.

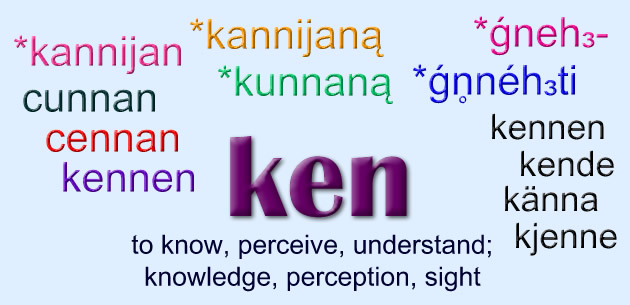

It comes from the old word agnail (a corn or sore on the toe or finger, torn skin near a toenail or fingernail), from Middle English agnail, from Old English angnægl, from ang (compressed, narrow, tight) and nægl (nail), from Proto-Germanic *naglaz (nail, peg), from Proto-Indo-European *h₃nogʰ- (nail). It was reanalyised as hang + nail in folk etymology [source].

Ang comes from Proto-Germanic *angus (narrow, tight) from Proto-Indo-European *h₂énǵʰus, (narrow, tight), from *h₂enǵʰ- (to constrict, tighten, narrow, tight, distresed, anxious) [source].

Words from the same root include anger, angina, angst, anguish, anxiety and anxious in English, ahdas (tight, narrow, cramped) in Finnish, cúng (narrow) in Irish, and узкий [ˈuskʲɪj] (narrow, tight) in Russian [source].

The word England possibly comes from the same root (at least the first syllable does) – from Middle English Engelond (England, Britain), from Old English Engla land (“land of the Angles”), from Proto-West Germanic *Anglī, from Proto-Germanic *angulaz (hook, prickle), from Proto-Indo-European *h₂enk- (to bend, crook), which may be related to *h₂enǵʰ- (to constrict, tighten, etc) [source].

Other names for hangnail include whitlow, wicklow, paronychia and nimpingang [source].

Whitlow comes from Middle English whitflaw. The whit part comes from Middle Dutch vijt or Low German fit (abscess), from Latin fīcus (fig-shaped ulcer), and the flaw part comes from Middle English flawe, flay (a flake of fire or snow, spark, splinter), probably from Old Norse flaga (a flag or slab of stone, flake), from Proto-Germanic *flagō (a layer of soil), from Proto-Indo-European *plāk- (broad, flat). [source]

Wicklow is a common misspelling of whitlow, and paronychia comes from Ancient Greek παρα (para – beside), and ὄνῠξ (ónux – claw, nail, hoof, talon) [source]

Nimpingang comes from Devonshire dialect and refers to “a fester under the finger nail”. Nimphing gang is an alternative version, and in West Somerset it is known as a nippigang. It comes from impingall (ulcer, infected sore), from Old English impian (to graft) [source] from Proto-West Germanic *impōn (to graft), from Vulgar Latin imputō (to graft), from Ancient Greek ἔμφυτος (émphutos – natural, (im)planted) [source]

Words from the same roots include imp (a small, mischievous sprite or a malevolent supernatural creature) in English and impfen (to inoculate, vaccinate) in German [source]