Podcast: Play in new window | Download

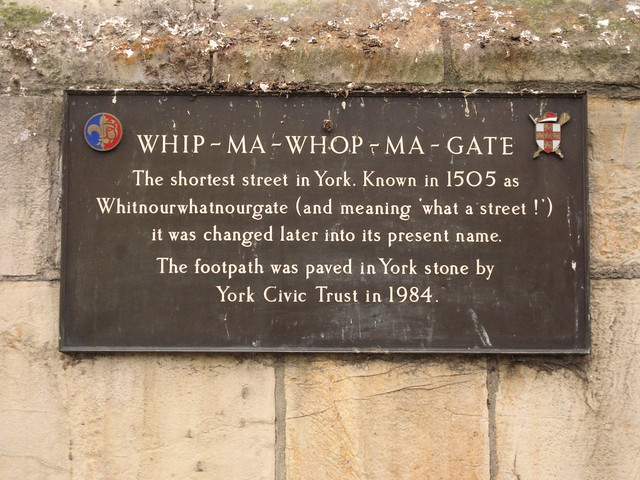

In today’s Adventure in Etymology we’re find out when a gate is not a gate.

A gate [ɡeɪt] is:

- A doorlike structure outside a house.

- A doorway, opening, or passage in a fence or wall.

- A movable barrier.

It comes from the Middle English gat(e)/ȝat(e) [ɡa(ː)t/ja(ː)t] (gate), from the Old English ġe(a)t/gat [jæ͜ɑt] (gate) from the Proto-West Germanic *gat (hole, opening) from the Proto-Germaic *gatą [ˈɣɑ.tɑ̃] (hole, opening, passage), from *getaną [ˈɣe.tɑ.nɑ̃] (to attain, acquire, get, receive, hold) [source].

In parts of northern England the word gate means a way, path or street, and in Scots it means way, road, path or street. It appears mainly in street names such as Briggate (“bridge street”) and Kirkgate (“church street”). It comes from the Old Norse gata (street, road), from the Proto-Germanic *gatwǭ [ˈɣɑt.wɔ̃ː] (street, passage), which comes from the same Proto-Germanic root as the other kind of gate.

Words from the same Old Norse root include gata [ˈɡɑːˌta] (street, frontage, strip) in Swedish, gate (street) in Norwegian and gade [ˈɡ̊æːðə] (street, road) in Danish, Gasse [ˈɡasə] (alley) in German, and gas [χɑs/ɣɑs] (unpaved street) in Dutch [source].

Here’s a video I made of this information:

Video made with Doodly – an easy-to-use animated video creator [affiliate link].

I also write about words, etymology, and other language-related topics, on the Omniglot Blog, and I explore etymological connections between Celtic languages on the Celtiadur.

You can also listen to this podcast on: Apple Podcasts, Amazon Music, Stitcher, TuneIn, Podchaser, PlayerFM or podtail.

If you would like to support this podcast, you can make a donation via PayPal or Patreon, or contribute to Omniglot in other ways.