Are the words hostage and host related? Let’s find out.

A hostage [ˈhɒs.tɪʤ / ˈhɑs.tɪʤ] is:

- A person given as a pledge or security for the performance of the conditions of a treaty or similar agreement, such as to ensure the status of a vassal.

- A person seized in order to compel another party to act (or refrain from acting) in a certain way, because of the threat of harm to the hostage.

other meanings are available.

It comes from Middle English (h)ostage (hostage), from Old French (h)ostage, either from Old French oste (innkeeper, landlord, host), or from Latin obsidāticum (condition of being held captive), from Latin obses (hostage, captive, security, pledge), from ob- (in front of) and sedeō (to sit) [source].

A host [həʊst / hoʊst] is:

- One which receives or entertains a guest, socially, commercially, or officially.

- A person or organization responsible for running an event.

- A moderator or master of ceremonies for a performance.

other meanings are available.

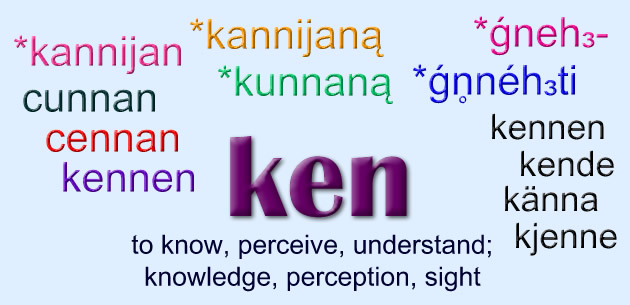

It comes from Middle English hoste (host), from Old French oste (innkeeper, landlord host), from Latin hospitem, from hospes (host, guest, visitor, stranger, foreigner, unaware, inexperienced, untrained), from Proto-Italic *hostipotis (host), from Proto-Indo-European *gʰóstipotis (lord, master, guest), from *gʰóstis (stranger, host, guest, enemy) and *pótis (master, ruler, husband) [source].

Host can also refer to a multitude of people arrayed as an army (e.g. a Heavenly host (of angels)). This comes from the same PIE root (*gʰóstis) as the other kind of host, via Middle English oost (host, army), Old French ost(e) (army), Latin hostis (an enemy of the state, a hostile), Proto-Italic *hostis (stranger, guest) [source].

Another meaning of host is the consecrated bread of the Eucharist. This comes from Middle English (h)oist (a sacrificial victim, the Eucharistic wafer), from Old French hoiste, from Latin hostia ( sacrifice, offering, victim, sacrificial animal, the consecrated bread), from Proto-Indo-European *ǵʰostiyo-, from *ǵʰes- (hand, to take, to give in exchange) [source].

So hostage and host might be related, at least in the first two senses.

Other words related to host include guest in English, Gast (guest) in German, gäst (guest) in Swedish, and gjest (guest) in Norwegian [source].

In Old English, the word ġīs(e)l [jiːzl] meant hostage, and comes from Proto-West Germanic *gīsl (hostage), from Proto-Germanic *gīslaz (hostage), from Proto-Celtic *geistlos (hostage, bail), from Proto-Indo-European *gʰeydʰ- (to yearn for). So a hostage is “one who yearns for (release)” [source].

Words from the same Proto-Celtic root (*geistlos), include giall (hostage) in Irish, giall (hostage, pledge) in Scottish Gaelic, gwystl (pledge, pawn, hostage) in Welsh, gijzelen (to take hostage) in Dutch, and Geisel (hostage) in German, gidsel (hostage) in Danish and gísl (hostage) in Icelandic [source].

Another word from the same Proto-Celtic root is kihlata (to betroth) in Finnish, which comes via Proto-Finnic *kihla (pledge, bet, wager, engagement gift), and Proto-Germanic *gīslaz (hostage) [source].