Things can be newfangled, but can they be oldfangled or just fangled?

Newfangled is used, often in derogatory, disapproving or humourous way, to refer to something that is new and often needlessly novel or gratuitously different. It may also refer to something that is recently devised or fashionable, especially when it’s not an improvement on existing things. It can also mean fond of novelty [source].

The word newfangle also exisits, although it’s obsolete. As a verb it means ‘to change by introducting novelties’, and as an adjective to means ‘eager for novelties’ or ‘desirous of changing’ [source]. It comes from the Middle English word neue-fangel, which meant fond of novelty, enamored of new love, inconstant, fickle, recent or fresh [source].

Things that are old-fashioned, antiquated, obsolete or unfashionable can be said to be oldfangled [source]. Things can also be fangled, that is, new-made, gaudy, showy or vainly decorated. Something that is fangled could be said to have fangleness [source].

The word fangle also exists, although it is no longer used, except possibly in some English dialects. It is a backformation from newfangled. As a verb it means to fashion, manufacture, invent, create, trim showily, entangle, hang about, waste time or to trifle. As a noun it means a prop, a new thing, something newly fashioned, a novelty, a new fancy, a foolish innovation, a gewgew, a trifling ornament, a conceit or a whim.

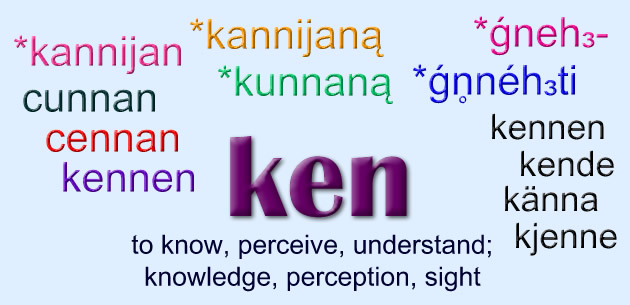

Fangle comes from the Middle English fangelen, from fangel (inclined to take), from the Old English *fangol/*fangel (inclinded to take), from fōn (to catch, caputure, seize, take (over), conquer) from the Proto-West Germanic *fą̄han (to take, seize), from the Proto-Germanic *fanhaną (to take, seize, capture, catch) [source].

Words from the same roots include fang (a long, pointed canine tooth used for biting and tearing flesh) in English, vangen (to catch) in Dutch, fangen (to catch, capture) in German, and få (to get, receive, be allowed to) in Swedish [source].