The Japanese word 曲 (kyoku) means a composition, piece of music, song, track (on a record), a tune, melody or air, or enjoyment, fun, interest or pleasure. Which is quite appropriate as music is enjoyable and fun for many people. It also often appears in the comments of the videos I watch that feature Japanese bands [source].

The same kanji when pronounced kuse means wrong, improper or indecent, or a long segment of a noh play forming its musical highlight. In the verb 曲がる (magaru) it means to bend, curve, warp, wind, twist, turn, be crooked and various other things, and as 曲げる (mageru) it means to bend, crook, bow, curve, curl, lean, tilt, yield and various other things.

曲 also appears in words like:

- 曲線 (kyokusen) = curve

- 曲がり角 (magarikado) = street corner, bend in the road, turning point, watershed

- 曲目 (kyokumoku) = name of a piece of music, (musical) number, (musical) program(me), list of songs

- 曲がりくねる (magrikuneru) = to bend many times, twist and turn, zigzag

- 曲芸 (kyokugei) = acrobatics

- 曲がりなりにも (magari nimo) = though imperfect, somehow (or other)

- 曲面 (kyokumen) = curved surface

曲目 (kyokumoku) sounds really nice to me, and something I struggle with is remembering the names of pieces of music. I can play quite a lot of tunes, but only know the names of some of them. I even forget the names of tunes I have written myself.

Here’s a little tune I wrote the other day called The Tower of Cats / Tŵr y Cathod.

In Chinese the character 曲 has several meanings: when pronounced qū it means bent, bend, crooked or wrong, and can also be a surname. When pronounced qǔ it means tune or song [source].

It appears in such words as:

- 曲子 (qǔzi) = tune

- 曲调 [曲调] (qǔdiào) = melody

- 曲折 (qūzhé) = winding, complicated

- 曲直 (qūzhí) = right and wrong

- 曲线 [曲線] (qūxiàn) = curve, curved line, indirect

- 曲解 (qūjiě) = to distort

- 曲别针 [曲別針] (qūbiézhēn) = paper clip

Sources: Line Dict CHINESE-ENGLISH, mdbg.com

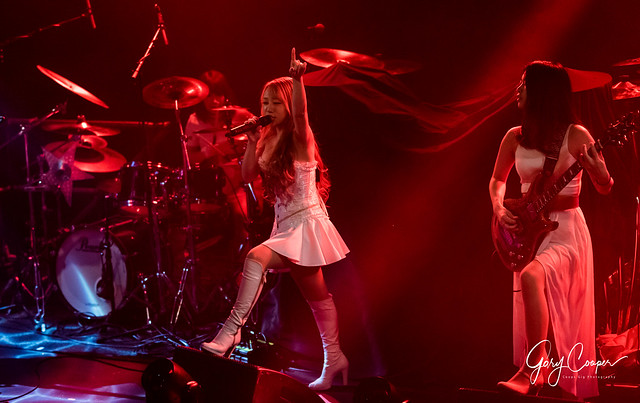

By the way, the band featured in the photo is Lovebites, a Japanese metal band who I really like.

This is their most recent video: