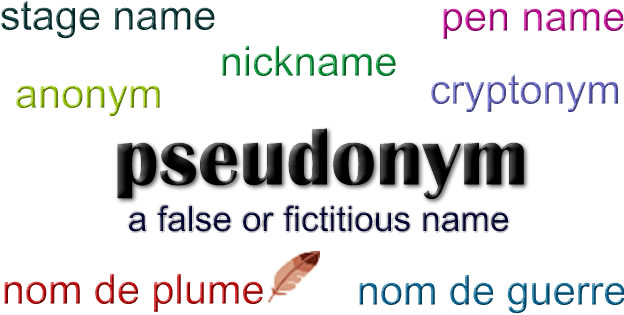

A pseudonym [ˈs(j)uː.də(ʊ).nɪm / ˈsu.də.nɪm] is a false or fictitious name, especially one used by an author. It comes from the Ancient Greek words ψευδής [pseu̯.dɛ̌ːs] (false, lying, untrue) and ὄνυμα [ó.ny.ma] (name) [source].

Hyponyms* include:

- stage name (used by actors)

- pen name, pen-name, nom de plume (used by writers)

- nom de guerre (used by military types)

- allonym = another person’s actual name adopted as a pseudonym

* a term that denotes a subcategory of a more general class [source].

Related words include:

- ananym = a pseudonym derived by spelling one’s name backwards

- anonym = an anonymous person, or an assumed or false name

- cryptonym = a secret name, or code name

An antonym of pseudonym is alethonym, which is the true name of an individual. From the Ancient Greek ἀλήθεια [aˈli.θi.a] (truth) and ὄνυμα [source].

I was inspired to write about pseudonyms today after seeing this joke on Facebook:

I used to go out with a girl called Sue Denim, until I found out that it wasn’t her real name.

It took me a while to get the joke, as I actually know someone called Sue Denim, a singer-songwriter who was part of the band Robots in Disguise. I always thought it was her real name, but now I realise that it’s actually an onomatopoeic pseudonym.

Do you have a pseudonym / nom de plume / stage name? If not, what pseudonym might you use?

I suppose the usernames I use online are kind of pseudonyms: Omniglot, Omniglossia and Ieithgi. Some variations of my name that I use, or friends use, include Sai, Simi and Saimundo.