Here’s a recording in a mystery language.

Do you know or can you guess the language?

If you are lost, you might say in French “j’ai perdu le nord”. It means literally that you have lost the north, and can also be translated as to lose one’s way or one’s bearings, to become dazed and confused, or to lose one’s marbles, to lose one’s head or to lose contact.

Alternatively you could say “je suis à l’ouest” (“I am in the west”), which means to be spaced out, to not be with it, or to lose one’s bearings.

Other words for confused in French include confus, perplexe and désorienté.

Confus (confused, confusing, ashamed, embarrassed), comes from Latin cōnfusus (mixed, united, confounded, confused), from cōnfundō ( to pour together, mix), from con- (with, together) and fundō (to pour, shed).

English words from the same roots include confound, confuse, diffuse, found, fuse and profound.

Perplexe (puzzled, perplexed, confused) comes from Latin perplexus (entangled, involved, intricate, confused), from plectō (I weave, I twist), from Proto-Indo-European *pleḱ- (to fold, weave). The English word perplexed comes from the same roots, via Old French.

Désorienté (disorientated, bewildered, confused) comes from désorienter (to disorientate, confuse), from dés- (dis-/de-) and orienter (to orientate, set to north, guide), from Old French oriant (Orient, the East), from Latin oriens/orentem (rising, appearing, originating, daybreak, dawn, sunrise, east), from orior (I rise, get up, appear, originate), from PIE *h₃er- (to stir, rise, move).

The English words disorentated and orientated come from the same roots, as do such words as orient, origin, random and run.

So when you’re disorientated, you’re not sure where the east is. These days maps are generally orientated towards the north, or in other words, north is at the top. However, in Medieval times, maps made by European cartographers were orientated towards the orient or east in the direction of Jerusalem and the Holy Land. Other orientations were and are available.

Why is north usually up on maps? The Map Men explain in this video:

Do you have any other interesting ways to say you’re lost or confused?

Here’s a song called “Ai-je perdu le nord ?” (Have I lost the north?) by Clio, a French singer:

Sources:

https://dictionary.reverso.net/english-french/confused

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/confus#French

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/perplexe#French

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/désorienté

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Category:English_terms_derived_from_the_Proto-Indo-European_root_*h₃er-

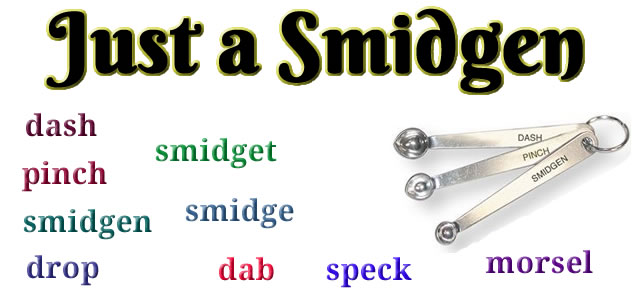

How much is a smidgen? How about a tad, dash, drop or pinch?

These are all terms that refer to small amounts of things. You might see them in a recipe, or use them to refer to other small quantities or amounts. You can even get measuring spoons for some of them.

Apparently a tad is ½ a teaspoon, a dash is ⅛ of a teaspoon. a pinch is 1⁄16 of a teaspoon, a smidgen is 1⁄32 of a teaspoon, and a drop is 1⁄64 of a teaspoon. Other amounts are available. A smidgen could be anything between 1⁄25 and 1⁄48, with 1⁄32 of a teaspoon being the most commonly used.

A tad is a small amount or a little bit, and used to mean a street boy or urchin in US slang. It probably comes from tadpole, which comes from Middle English taddepol, from tadde (toad) and pol(le) (scalp, pate).

A dash is a small quantity of a liquid and various other things. It comes from Middle English daschen/dassen (to hit with a weapon, to run, to break apart), from Old Danish daske (to slap, strike).

A smidgen is a very small quantity or amount. It is probably based on smeddum (fine powder, floor), from Old English sme(o)dma (fine flour, pollen meal, meal). Or it might be a diminutive of smitch (a tiny amount), or influenced by the Scots word smitch (stain, speck, small amount, trace). Alternative forms of smidgen include smidge, smidget, smidgeon and smidgin.

A pinch is a small amount of powder or granules, such that the amount could be held between fingertip and thumb tip, and has various other meanings. It comes from Middle English pinchen (to punch, nip, to be stingy), from Old Northern French *pinchier, possibly from Vulgar Latin *pinciāre (to puncture, pinch), from *punctiāre (to puncture, sting), from Latin punctiō (a puncture, prick) and *piccāre (to strike, sting).

A drop a very small quantity of liquid, or anything else. It comes from the Middle English drope (small quantity of liquid, small or least amount of something) from Old English dropa (a drop), from Proto-West Germanic *dropō (drop [of liquid]), from Proto-Germanic *drupô (drop [of liquid]),from Proto-Indo-European *dʰrewb- (to crumble, grind).

Do you know any other interesting words for small amounts or quantities?

Sources:

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/smidgen#English

https://practical-parsimony.blogspot.com/

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/tad#English

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/dash#English

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/pinch#English

https://quod.lib.umich.edu/m/middle-english-dictionary/dictionary/

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/smidgen#English

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/drop#English

Jot and Tittle – it would be a good name for firm of printers, but actually means a smallest detail or the smallest details. It is often preceded by every, as in “every jot and tittle”.

A version of this phrase appears in the Bible (Matthew 5:18):

For verily I say unto you, Till heaven and earth pass, one jot or one tittle shall in no wise pass from the law, till all be fulfilled.

Another example include “He did not get every jot and tittle, but the plan ultimately adopted was viable.”

Jot can refer to:

It comes from Latin iōta (a Greek letter), from Ancient Greek ἰῶτα (iôta [Ι ι] – a letter in the Greek alphabet; a very small part of writing). The name of the letter comes from Phoenician 𐤉 (y – yōd/yodh), which comes from Proto-Semitic *yad- (hand). The letter is based on an Ancient Egyptian hieroglyph meaning hand or arm (𓂝).

The English word iota (a jot, a very small, insignificant quantity) comes from the same roots.

Tittle can refer to:

It comes from the Middle English title / titel(e) (inscription, small mark or stroke made with a pen), from Anglo-Norman titil, from Medieval Latin titulus (title of a book, heading, tablet, inscription, epitaph), which probably comes from Etruscan.

Words from the same roots include tilde (e.g. ã, ñ, õ), and title in English, and tildar (to declare, brand, stigmatize, put a tilde or other accent mark over, to go into a trance) in Spanish.

Sources:

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/jot_and_tittle

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/jot#English

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/iota#English

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/tittle#English

https://quod.lib.umich.edu/m/middle-english-dictionary/dictionary/

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/tildar#Spanish

Last night some actual French people came to the French conversation group – a couple (Giles et Carmen) from Saint-Étienne in the southeast of France who are friends of a friend.

One interesting thing they said is that there is a local form of speech unique to Saint-Étienne and the surrounding area which they refer to as patois. Apparently it doesn’t have any other names they’re aware of.

The city of Saint-Étienne is part of the Loire département and is home to about 174,000 people, and the metropolitan area it’s part of, Saint-Étienne Métropole, has about 497,000 inhabitants. It was an industrial city and a major coal mining centre, and has become a centre for design [source].

The population apparently comes from many different places, so the local speech includes words from various regional forms of speech. The city is named after Saint Stephen, a.k.a. Sanctus Stephanus de Furano (Saint-Étienne of Furan) [source], and the local people are known as Stéphanois (masculine) and Stéphanoises (feminine). So perhaps the local dialect could be called Stéphanais (Stephenish)?

I should have done this before, but I just searched for “patois de Saint-Étienne” and discovered that it does have a name (several, in fact): le gaga, le parler gaga, le parler stéphanois or l’arpitan stéphanois in French, and Parlâ Gaga in the language itself. These refer to a variety of Franco-Provençal / Arpitan spoken in the area, and a regional form of French spoken there that has influences from that language [source].

Here’s an example of Parlâ Gaga:

Lou rat de villa et lou rat dos champs

Djins lou tchion, ün rat de villa

Doutà de noblous ponchants,

Fit dj’una façonn civila,

Mandâ soun frâre dos champs.

Un repas de bateyailles

Serre fat djïns sa meissoun ;

Par assures les voulailles

Vou’erre dounc bion de seisoun.

Here it is in the original French:

Le rat des villes et le rats des champs

Autrefois le Rat de ville

Invita le Rat des champs,

D’une façon fort civile,

A des reliefs d’Ortolans.

Sur un Tapis de Turquie

Le couvert se trouva mis.

Je laisse à penser la vie

Que firent ces deux amis.

Source: http://gagaweb.chez.com/ratville.htm

Here are examples of spoken Parlâ Gaga:

More information about Parlâ Gaga:

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parler_gaga

https://fr.wiktionary.org/wiki/Annexe:Glossaire_du_parler_gaga

http://gagaweb.chez.com/