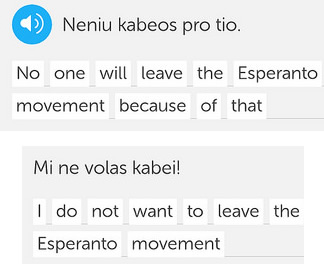

The word kabei [ka.ˈbe.i] appears in one of the Duolingo Esperanto lessons I did today in the sentences, “Mi ne volas kabei” and “Neniu kabeos pro tio”.

From the words available for the translation, I worked out what it meant, but it’s not obvious. In order to understand this word, you have to know something about the history of Esperanto.

Kabei means “to leave the Esperanto movement”, so the first example means “I don’t want to leave the Esperanto movement”, and the second means “Nobody will leave the Esperanto movement because of that”.

This word is based on the pseudonym, Kabe, which was used by Kazimierz Bein (1872-1959), a Polish ophthalmologist and prominent member of the Esperanto movement. He wrote prose in Esperanto, translated novels into the language, and produced one of the first Esperanto dictionaries. At least until 1911, when he left the movement, without saying why. In 1931 Bein said that he didn’t think Esperanto was a viable solution for an international language.

Not long after he left the Esperanto movement his pseudonym became a Esperanto word meaning “to fervently and successfully participate in Esperanto, then suddenly and silently drop out”.

Another word that’s very specific to Esperanto that came up in today’s lessons is krokodili (lit. “to crocodile”), which means “to speak among Esperantists in a language besides Esperanto, especially one’s native language or a language not spoken by everyone present” [source], for example “Ne krokodilu!” (Do not speak your native language when Esperanto is more appropriate!).

The origins of this word are uncertain. It may be related to crocodile having large jaws, and to the action of flapping one’s jaws carelessly. Maybe is was used to refer to noisy non-Esperantists who disturbed an Esperanto group in Paris in the 1930s. Or it may come from Andreo Cseh, an Esperanto teacher who’s students had to speak Esperanto when holding a wooden crocodile he always had with him [source].

The antonym of krokodili is malkrokodili, which means “to speak Esperanto among non-Esperanto speakers”.

You could use both words together perhaps: “Li ĉiam krokodilis, kaj pro tio li devis kabei.” (He always spoke his native language instead of Esperanto, and therefore he had to leave the Esperanto movement).