Here is part of a song in a mystery language.

Can you identify the language, and do you know where it was spoken?

Clue: this is an extinct language and the lyrics of the song are based on an ancient inscription.

Here is part of a song in a mystery language.

Can you identify the language, and do you know where it was spoken?

Clue: this is an extinct language and the lyrics of the song are based on an ancient inscription.

– la caisse (enregistreuse), le tiroir caisse = till / cash register = cofrestr arian = kefierez

– la caisse automatique = self-service till / self checkout = cofrestr arian awtomatig = kefierez emgefre

– casissier = checkout assistant = gweithiwr cofrestr arian

– vendeur (-euse) = shop assistant = gweithiwr siop = gwerzher

– l’hydromel (m) = mead = medd = chouchenn, dour-mel

– affolé = panic-stricken = llawn braw, rhuslyd, gwyllt

– affolant = disturbing = cynhyrfus, annifyr, cythryblus = da bennfollañ, braouac’hus

– affoler = to terrify = dychryn, brawychu, arswydo

– s’affoler = to (get into a) panic = cynhurfu, rhusio, dychryn = pennfollañ

– ne t’affole pas! = don’t panic = paid â chynhyrfu!

Last night at the French conversation group one of the things we talked about was shopping, particularly in supermarkets, and one of the words we weren’t sure of was till / cash register. I now know this is la caisse (enregistreuse) or le tiroir caisse and that someone who works on a till is possibly un caissier or une caissière.

This got me thinking what you call such a person in English. You might call them a shop assistant or maybe a cashier, but neither of these seems to fit the job very well.

What would you call such a person? Would the term you use depend on the kind of shop?

Today we have a guest post by Jade Henriques, a young language learner who is planning to pursue a degree in linguistics. Here is her website languageninjas.com. You can also keep up with Facebook.

From the first time I started learning languages, I see this question pop up from time to time. I too considered if I was just too old to learn another language. The thing is that people believe that you have to be at a certain age to learn a language, once you pass this age learning a language is next to impossible.

On the contrary scientist may disagree; I’ve actually stumbled across many researches that say; not learning a language because of your age is a myth. When it comes to learning a language, adults actually have the capability of learning faster than little children. One perspective I have is that as adults we already learned the basics of communication and the meaning of objects around us. For example, a seven year old may learn that a tree is a plant, a tree has leaves, and a tree grows from the soil. As adults we know this already, in our second language all we need to know is what a tree is in that language, we don’t need to go into details of what it is or a description of it.

It’s still, however, an ongoing battle of whether children learn better or adults do.

Our Brains can actually do it

The human brain is still a mystery to many scholars and scientists out there. The complexity of it is baffling. Something I see so very often is that if we see a word 160 times over, it is permanently lodged into our permanent memory. That doesn’t mean you should sit and say a word 160 times over. It means that if over a period of time, on different occasions, if you see a word at least 160 times, it’s going to be hard to forget that word. This research was carried out by a group of Cambridge neuroscientists. This is why reading is so important when learning a language. The first time you see a word and you don’t understand it, don’t beat yourself up. If you were to see this word again, and again and again, our brains will begin to make sense of it and remember it for us.

It’s about inputting

There is no way on God’s earth you can speak a language with very little input. It is in the same essence if you see a word for the first time and you don’t understand it right of the back, then that simple means you hardly see this word or you’ve never seen this word before. So, before you open your mouth, start inputting data into your brain.

I’ve find that it is actually easier to remember words when we are not fighting ourselves to remember them. For instance, making vocabulary list and spending your day studying this list is not the way to go.

But naturally just reading and listening (to things you actually enjoy) will help you to remember words faster and pain free.

Long term, Medium term and short term memory

Long term memory is words that we will never forget. Long term memory is very hard to destroy and it would take a brain disorder such as Alzheimer’s to do so. This is what the above study suggests that if a word is seen 160 times, then it’s a part of your long term memory. With words in your medium term memory, it suggests that you have seen these words numerous times but not enough. If you neglect these words over a period of time, chances are you will forget them. Words in your short term memory are the easiest to forget, maybe you just seen these words a handful of times, overtime, try to make words in your short term memory apart of your long term memory.

In conclusion, you are not too old to learn a language; it’s just a matter of practice and a passion for the language.

According to an article I came across today, it is the process of learning a new language that encourages people to learn more languages, and becoming bilingual makes learning further languages easier.

The article talks about at study of native English speakers who were either monolingual, or bilingual in English and Spanish or English and Mandarin, and who were presented with words made up by the researchers. It found that the bilingual participants could learn the made up words much more easily than the monolingual ones, and the researchers think that the process of learning a foreign language improves your language learning skills.

Another study found that bilinguals are also better at learning words in their native language and generally have faster brain activity, especially older adults (60-68 years old) who have been bilingual from an early age. Apparently “these results suggest that lifelong bilingualism may exert its strongest benefits on the functioning of frontal brain regions in aging.”

Here’s some text from a book I’m currently reading in which some of the dialogue is written in this way. Do you have any idea where people speak like this?

“Vares nuffing nú unnersun, mì sun. Doan ask wy ve öl daze wuz bé-er van vese, coz U aynt gó ve nous fer í. Lemme tellya, no geezer az a clú abaht iz own tyme, yeah? Ees juss lyke a sparrer, eggzackerly lyke a sparrer aw a bitta bá-erred cod.”

Another bit:

“E oo ayts lyf wil keep í, thass wot í sez in ve Búk, innit? Wel, Eye doan luv lyf ennymaw wivaht Am, so Eye spose Eye must ayt í. Awl Eye did woz 4 Am, awl Eye evah wannid woz 4 uss ló 2 B cumfy.”

Note: as far as I know, this form of speech is rarely written, and this spelling system seems to be one developed by the author. The second quote is in a future version of the form of speech used in the first one.

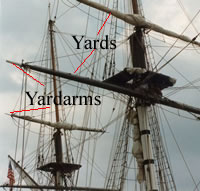

Last night there was some discussion of the phrase ‘when the sun is over the yardarm’ and none of us were sure what a yardarm or even a yard is. I suspected that there were part of the rigging of a sailing ship, but wasn’t sure which part.

I now know that a yard is a spar, or long piece of wood or metal attached to the mast of a sailing ship to which the sails are attached, and that a yardarm is the end of a yard (see photo).

The phrase ‘over the yardarm’ refers to the practise of officers on sailing ships of waiting until the sun appeared to above a particular yardarm before having their lunch or first alcoholic drink of the day. In summer in the north Atlantic this would be at about 11am. This became the time when the sailors received their first ration of rum, and the officers stuck to this time even when ashore. The expression spread to landlubbers and is still quite widely used, especially in North America. On land the sun appears over the proverbial yardarm at around 5pm. It first appeared in print in Rudyard Kipling’s From Sea to Sea in 1899. [from World Wide Words and Wikipedia].

– apprenti(e) = apprentice = prentis = deskard

– apprentissage = apprenticeship = prentisiaeth = deskardelezh

– le porte-clefs/porte-clés = key ring / chain / fob = torch allwedd = doug alc’hwezoù

– l’anneaux porte-clefs = key ring = torch allwedd = (?)

– une clé/clef de rechange / une autre (clef) = spare key = allwedd sbâr = alc’hwez da drok (?)

– un roue de rechange/de secours = spare wheel = olwyn sbâr = rod-eskemm

– l’ouïe (f) = hearing = clyw = kleved / klev

– être dur(e) d’oreille = to be hard of hearing = bod yn drwm dy glyw = bezañ fall e gleved, bezañ teñvalglev

– la brasserie = brewery = bracty, bragdy = bierezh, breserezh

– (nez) camus = pug nose = trwyn smwt = fri-togn

I came across an interesting-looking site today called Linguisticator, via the Economist.

It says that it provides “an advanced online language training program designed to teach adults how to learn languages quickly and effectively. It is unique in providing a single course that can be used to learn any language on the planet. The program was designed with military and business professionals in mind, but is available to anyone serious about learning a language.”

Apparently, “With the training Linguisticator provides, it’s possible to learn languages faster and more accurately than children do, such that you can gain conversational competence in only a few weeks and fluency in a few months.”

It’s basically a video-based course that you subscribe to and watch online. It doesn’t teach a particular language, but teaches you how to learn languages systematically. You can also book individual language lessons via the website and work out a language learning plan.

There’s a free trial version that gives you a taster of the course.

Have any of you tried it?

What’s the connection between newspapers and magpies?

Well, apparently the first newspapers published in Venice and were known as gazeta de la novità and cost one gazeta (Venetian) or gazzetta (Italian), a small coin which had a picture of a magpie on it. A magpie is gazza in Italian and the name of the coin is a diminutive form of that name. Another possibility is that the newspaper was named after the magpie, a bird renowned for chattering.

The word gazette was first used in English in 1665 for a newspaper published in Oxford [source].