Ta mee ayns thie m’ayr as my voir rish shiaghtin dy leih nish. Ta’n lught thie aym ayn ayns shoh – my voir, my vraar, as my huyr as my vraar ‘sy leigh as ny kiyt oc. Agh dy meeaighar cha nel m’ayr ayn – hooar eh baase yn çhiaghtyn shoh chaie. V’eh 74 bleeaney d’eash as cha row eh çhing, as hooar shin greain agglagh tra hooar ee baase dy doaltattym jeh teaym chree moghrey ‘sy voghree Jecrean.

Va shirveish ny merriu ayn Jerdein yn çhiaghyn shoh as va ram sleih ayn. Hug my vraar, shenn co’obbree m’ayr as yn saggyrt moyllejyn yindyssagh, as ec yn farrar ny yei yn shirveish, haink mee ny quail ram sleih nagh vel mee er n’akin ad rish foddey dy hraa.

Mairagh hem er-ash dys Bangor, as hed my huyr, my vraar ‘sy leigh as ny kiyt oc er-ash dys Plymouth, agh ta cooney ry-gheddyn er my voir rish yn pobble ynnydagh ‘syn balley beg shoh.

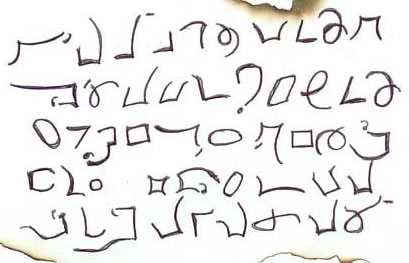

M’athair

Tá mé i dteach mo thuismitheoirí ar feadh seachtaine go leith anois. Tá an teaghlach ar fad anseo – mo mháthair, mo dheartháir, agus mo dheirfiúr agus mo dheartháir céile agus a gcait. Ar an drochuair, níl m’athair ann – fuair sé bás an seachtain seo caite. Bhí sé 74 bliain d’aois agus ní raibh sé tinn, agus baineadh croitheadh asainn nuair a fhuair sé bás go tobann le taom croí go luath ar maidin Dé Céadaoin.

Bhí seirbhís na marbh ann Déardaoin an seachtain seo agus bhí a lán daoine ann. Thug mo dheartháir, sean chara agus comhghleacaí m’athair agus an biocáire ómós corraitheach, agus i ndiaidh an seirbhís, bhuail mé leis go leor daoine nach bhfuil mé ag bualadh leo le blianta.

Amárach rachaidh mé ar ais go Bangor, agus rachaidh mo dheirfiúr, mo dheartháir céile agus a gcait ar ais go Plymouth, ach tá cuidiú agus tacaíocht le fáil ag i bpobail i sráidbhaile beag seo.

Fy nhad

Dw i wedi bod yn nhŷ fy rhieni ers wythnos a hanner erbyn hyn. Mae’r teulu yma – fy mam, fy mrawd, a fy chwaer a brawd-yng-nghyfraith ac eu cathod. Ond yn anffodus dydy fy nhad ddim yma – mi wnaeth o farw yr wythnos diwetha. Roedd o’n 74 blwydd oed a doedd o ddim yn sâl, ac mi wnaethon ni sioc mawr pan wnaeth o farw efo trawiad ar y galon yn gynnar fore Mercher.

Roedd yr angladd Ddydd Iau yr wythnos hon ac roedd cryn dipyn o bobl yna. Mi wnaeth fy mrawd, hen gydweithiwr a’r ficar teyrngedau hyfryd, ac mi wnes i cwrdd â llawer o bobl mod i ddim wedi eu weld ers amser maith yn yr derbyniad ar ôl yr angladd.

Yfory bydda i’n mynd yn ôl i Fangor, ac bydd y chwaer, fy mrawd-yng-nghyfraith ac eu cathod yn mynd yn ôl i Plymouth, ond mae cymorth ar gael ar gyfer fy mam yn nghymuned agos y pentref bach ‘ma.