Can any of you translate the following bit of Czech into English – “Zdravím předladatele”?

A visitor to Omniglot has asked for help with this.

A Japanese company has come up with a gizmo called a Tele Scouter / テレスカウター which can translate what people say to you in foreign languages and display the results via a retinal display attached to your glasses.

The Tele Scouter is a small gadget that fixes onto glasses which incorporates a retinal display, a camera and a microphone. The microphone picks up the language and transmits it to a small computer worn around the waist, which sends it to a server for translation. The translation is then displayed on the retina. The device cannot currently keep up with language spoken at normal speed, and is a bit bulky, but it’s an interesting development.

If the size can be reduced and the speed and reliability increase, this device could be really useful. If it could also translate and/or transliterate written language, if would be even more useful, especially in for languages written with different writing systems.

Emilio Gonzalez, who works as an intercultural mediator with immigrant children in Tenerife, emailed me to see if I could help to translate a short story into as many languages as possible.

Here’s the original Spanish version, and the English version:

Érase una vez un ratón que salió de su madriguera y se encontró un enorme león.

El león quería comérselo.

– Por favor, león no me comas. Puede que un día me necesites.

El león le respondió:

-¿Cómo quieres que te necesite, con lo pequeño que eres?

El león se apiadó al ver cuán pequeño era le ratón y lo soltó.

Un día, el ratón escuchó unos rugidos terribles.

Era el señor león.

Cuando llegó al lugar, encontró al león atrapado en una red.

– íYo te salvaré! – dijo el ratón.

¿Tú? Eres demasiado pequeño para tanto esfuerzo.

El ratón empezó a roer la cuerda de la red y el león pudo salvarse.

Desde aquella noche, los dos fueron amigos para siempre.

Once upon a time there was a little mouse who, coming out of his hole, met an enormous lion.

The lion wanted to eat him up.

“Please, Mr. Lion, don’t eat me. One day you might need me.”

The lion answered, “Why should I need someone as small as you?”

Seeing how tiny the mouse was, the lion took pity on him and set him free.

One day, the mouse heard an almight roar.

It was the lion.

When he got to the place, he found the lion trapped in a net.

“I’ll save you!” said the mouse.

“You?” You are too small for such a hard task.”

The mouse started to nibble at the rope of the net and the lion was saved.

From that day on they were friends forever.

The story has already been translated into Catalan, Basque, France, Portuguese, German, Arabic and Chinese, as well as English. Here’s a pdf with those translations.

Could you translate it into any other languages?

If you can help, please email Emilio at: animaccion[at]gmail[dot]com

A translation agency has contacted me asking for help finding someone who can translate from English to Fijian.

If you can do this, or know someone who can, please contact Stephen at stealthtranslations@googlemail.com as soon as possible.

Thank you / Vinaka

Lowlands-L Anniversary Celebration is an interesting website I discovered recently which features translations of a Low Saxon / Low German folktale, De Tunkrüper (The Wren), in numerous languages. There are also details of the languages and recordings of some of the translations. The author of the site, Reinhard F. Hahn, is keen to collect translations and recordings of the story in as many languages and dialects as possible – perhaps you can help.

The Lowlands-L website contains information about the West Germanic languages of the lowlands along the North and Baltic seas, including many varieties of Dutch, Frisian, Low Saxon and English. The Anniversary Celebration section concentrates particularly on those languages, but also includes languages from many other parts of the world, as well as constructed languages, and extinct languages such as Gothic and Coptic.

Today we have a guest post by Paul Sawers, a Communications Executive at Lingo24.

As one of the few mono-linguists working for a very multi-lingual translation company (Lingo24 – even the programmers can speak at least two languages…), I certainly don’t think I’m in any less of a position to comment on some of the linguistic lapses that seem to be everywhere in society.

Indeed, whilst my rudimentary French and Spanish is probably enough to get me a room for a night in a Paris or Madrid hotel, my language skills pale in comparison to the Account Managers, Project Managers, IT specialists and marketing personnel I work with on a daily basis. And all this before we even begin to discuss all the trusted translators we work with.

But alas, whilst it has always been an ambition of mine to become proficient enough in Spanish so I can at least hold a decent conversation with a native Spaniard, it isn’t necessary for my job. I simply manage the English-language side of our communications.

Having been immersed in the translation industry for the best part of 6 months now, I certainly feel as though I’ve learned a lot about the industry. From simple things like the difference between a translator and an interpreter, to the importance of using qualified linguists rather than laypeople that just happen to be fluent in another language.

These may be things that many people take for granted, but for someone who has never worked in the languages industry, these are things I’d never really considered before.

But at any rate, the purpose of this post isn’t to dwell on life in a translation agency, it’s really more about how it’s made me more aware of other languages in general.

Lingo24 is regularly asked why someone should use a professional translation service when there is a plethora of software and free online translation tools widely available. Well, there are many examples which help to illustrate why machine translation tools perhaps aren’t the most reliable route to go down.

Last year, there was the restaurant in China that, whilst obviously trying to make its shop-front more appealing to the English-speaking world for the Summer Olympics, decided to use an online translation tool: ‘Translate Server Error’ was the resulting message, designed to ‘entice’ anglophiles through its doors.

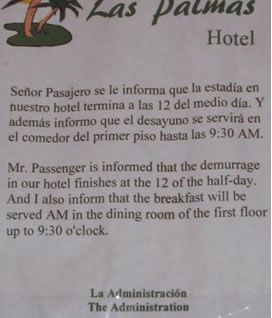

And whenever I’m abroad now, I’m always on the lookout for dodgy translations. On a recent trip to South America, I was staying in a hotel in Arica, a small town in northern Chile.

There was a sign on the door of our hotel room which was designed to inform English-speakers of the check-out time and breakfast details.

I had to take a photograph of the sign, as it did make me laugh. Being referred to as ‘Mr. Passenger’, and the ‘demurrage’ finishing at ‘12 of the half-day’, certainly brightened my morning. But as easy as it is to mock online translation tools – which were evidently used on this occasion – what would the alternative have been?

My Spanish wasn’t great. And their English was roughly about the same. But they were considerate enough to take the time to provide a sign which DID get the message across, and saved me a great deal of time in terms of thumbing through my trusted Lonely Planet phrase book.

So, I guess my point is, there is a time and a place for online translation tools. And this situation clearly fitted the bill. But it also helps to confirm that for any business that is serious about its communications, machine translation tools perhaps aren’t quite up to the task.

Have you ever wondered what kind of challenges you might encounter when translating Asterix? It’s not just about translating the dialogues – there are also numerous names, verbal and visual puns, songs and accents to deal with, and you have to fit the translated text into the speech bubbles. An interesting site – Literary Translation – goes into more detail of some of the difficulties of translating various literary works, including Asterix.

I’ve only read Asterix in English, plus a few of the books in German, so am not familiar with the original French text. Most of the names of the characters in French are different to the ones I’m used to in English. For example, the Gaulish bard, who is Cacofonix in English, is known as Assurancetourix = assurance tous risques, ‘comprehensive insurance’ in French. Many of the other names are made up of French words like this, and don’t sound like names if translated literally. Another example is the Gaulish chieftain, Abraracourcix, whose name comes from the phrase

There are many sites that translate between different languages, but a site I found today called Sign Translate is the first one I’ve seen that translates between English and sign language.

The site is intended for health professionals working in Britain’s NHS (National Health Service) and provides translations from English to and from British Sign Language (BSL), and also between English and Arabic, Bengali, French, Gujarati, Korean, Polish, Portuguese, Punjabi, Somali, Spanish, Turkish and Urdu. The BSL translations are displayed as videos, while translations in the others languages are available as text and audio.

The system does not in fact translate anything you say to it; instead it is programed with a set of typical questions and answers used in medical situations with versions of these in BSL and the other languages. Online BSL interpretation by real interpreters using webcams is also available.

This kind of system could be useful in other places such as hotels, police stations, banks, etc.

Have you come across any similar systems?

There’s a saying in English that goes something like this: “don’t criticise someone until you’ve walked a mile in their shoes”. A corollary that’s sometimes added is: “If they don’t like your criticism, you’ll be a mile away and you’ll have their shoes”.

Aislinn Thomas, whose blog, In Your shoes, describes how she puts this saying into practice by actually wearing other people’s shoes for a day, is looking for equivalents of this phrase in other languages. Can you help?

Most British managers think they should make more effort to learn about the business practices of other countries before visiting them, and two thirds find their lack of knowledge about other cultures embarrassing, according to an article I found today.

A survey of just over 200 senior managers and directors of major UK companies found that the vast majority rely on their foreign colleagues being able to speak English, only one fifth said they spoke another language, and a quarter of them admitted making cultural faux-pas when dealing with foreign business people. In spite of this, 80% said that they often do business with people from other cultures, and 66% said they travel overseas regularly on business.

Perhaps what they need are cultural interpreters, who could accompany them on their trips and explain the culture and etiquette of the countries they visit, maybe acting as interpreters of language as well. Do such people exist?