Here’s a recording in a mystery language.

Can you identify the language, and do you know where it’s spoken?

Here’s a recording in a mystery language.

Can you identify the language, and do you know where it’s spoken?

Today we have a guest post by Tim Brookes, founder of the Endangered Alphabets Project.

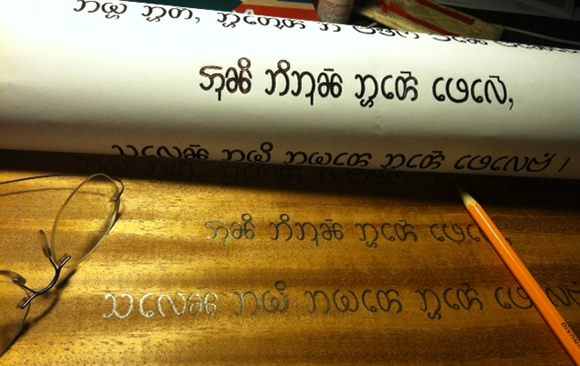

As some of you know (in part because Simon has been kind enough to publicize my work on Omniglot), I’ve been spending the past three years gathering texts in writing systems that seem in danger of extinction, and then carving those texts in gorgeous pieces of wood, as a twin act of preservation and celebration.

Now a new and urgent Endangered Alphabets situation has arisen, in a region of southern Bangladesh called the Chittagong Hill Tracts. This upland and forested area is home to 13 different indigenous peoples, each of which has its own genetic identity, its history and cultural traditions, and many of which have their own language and even their own script.

All these languages and scripts are endangered. Schools use Bengali, the official national language, and an entire generation is growing up without a sense of their own cultural history and identity. This is very much the kind of situation that has led to the loss or endangerment of hundreds of Aboriginal languages in Australia and Native American languages in the US. And this loss of cultural identity is closely connected to dropout rates in schools, unemployment, poor health—all the signs of cultural decay and collapse.

The Endangered Alphabets Bangladesh project is an attempt to provide a creative solution to this issue before these languages and scripts are among the estimated 3,000 languages that by mid-century will be lost forever.

I’m trying to help by starting a Kickstarter fundraising campaign and forming a coalition of artists and academics from Harvard, Yale, Cambridge, Oxford and Barcelona. We’re going to be working with an extraordinary young man named Maung Nyeu.

Largely self-educated because he couldn’t speak the Bengali used in school, Maung left Bangladesh and got into the University of Hawaii, where he studied engineering so he could go back to the Chittagong Hill Tracts and build a school where indigenous peoples could be educated in their own languages. Now he has come to Harvard to get a graduate degree in education so he can create something unique: children’s schoolbooks in these endangered indigenous languages.

He says, “I’m trying to create children books in our alphabets – Mro, Marma, Tripura, Chakma and others. This will help not only save our alphabets, but also preserve the knowledge and wisdom passed down through generations. For us, language is not only a tool for communications, it is a voice through which our ancestors speak with us.”

We’re trying to help him by combining three artistic disciplines: carving, calligraphy and typography.

The first step is for me to create a series of beautiful and durable carved signs in the languages and scripts of these endangered cultures, and add them to the traveling exhibitions of the Endangered Alphabets Project. Each carving will feature a short poem I wrote for the purpose. It goes:

These are our words, shaped

By our hands, our tools,

Our history. Lose them

And we lose ourselves.

Our coalition, which includes a typographer and a calligrapher, will create some beautiful script forms of these endangered languages, then convert them into typefaces that can be used to print the books for Maung’s school.

At the moment, everyone is putting in their time on a volunteer basis, but my goal is to raise $10,000 to cover material costs, and to go a small way toward paying for the time, work, travel, shipping and printing involved.

If we can raise these funds, the outcome will be the first sets of children’s schoolbooks ever printed in Mro, Marma, Chakma, and other endangered languages of Bangladesh.

If you’d like to help, please visit the Kickstarter For Bangaldesh site, or pass this link along to others who might want to help.

Thanks!

– le moine / le religieux = monk = mynach

– le monastère = monastery = mynachlog

– la (bonne) sœur / la religieuse = nun = lleian

– le couvent = nunnery / convent = lleiandy / cwfaint

– se vanter = to boast = brolio / ymffrostio

– la vantardise = (a) boast = brol / ymffrost

– épais = thick = trwchus / tew

– mince / fin / maigre = thin = tenau / main / cul

– une brebis galeuse = black sheep (“mangy ewe”) = dafad ddu

– à chaque troupeau sa brebis galeuse = there’s a black sheep in every flock = y mae dafad ddu ym mhob praidd

– le champ des courses = racecourse = cae rhedeg

– s’éndormir = to fall asleep = syrthio / cwympo i gysgu

– endormi = asleep = yn cysgu / ynghwsg

– à moitié endormi = half asleep = yn hanner cysgu

– la roche = rock (substance) = craig

– le roc = rock (hard, solid) = craig (galed)

– le rocher = boulder / rock = clogfaen / craig

Recently I came across the word noodling which in the context referred to singing an improvised sort melody made up of nonsense syllables over the top of a song. I hadn’t encountered this usage before so remembered it. I thought this sort of thing would be called improvisation or scat singing. Have you heard of noodling use in this way.

According to the OED, a noodle can be a stupid or silly person; a slang term for the head; long string-like pasta-type stuff; or a trill or improvisation on an instrument (mainly in jazz).

According to Wikipedia noodling “is fishing for catfish using only bare hands, practiced primarily in the southern United States.” Other names for this activity include catfisting, grabbling, graveling, hogging, dogging, gurgling, tickling and stumping. I’ve heard of tickling for trout, but never of noodling for catfish, or those other terms.

The Free Dictionary lists a number of noodle related phrases:

– to noodle around = to wander around; to fiddle around with something

– to noodle over something = to think about something.

– to use one’s noodle = to use one’s head/brain

Have you heard or do you use any of these expressions? If not, what equivalents might you use?

If you say that you ‘know’ a particular language, what does that mean to you?

1. Does it mean that you know some words and phrases and can ‘get by’ in ordinary tourist-type situations?

2. Does it mean that you can participate in conversations in the language on topics familiar to you, even if you stumble over words and make mistakes?

3. Does it mean that you can speak (and understand, read and write) the language with a fluency that you feel is sufficient for your needs?

4. Does it mean that you speak (and understand, read and write) the language with native-like pronunciation and fluency?

5. Does it mean that your knowledge of the language is comparable to a well-educated native speaker, i.e. that you not only speak, understand, read and write the language well, and know how to use it in different contexts (pragmatics), but you’re also familiar with and identify with the culture. The idioms make sense to you, and you get the jokes and references to people, events, places, etc. Maybe you also feel a deep attachment to the language and culture.

Or maybe you have a combination of abilities – e.g. the ability to understand and read the language, at least to some extent, some spoken ability, plus some familiarity with the culture.

No 5 is based on a definition of knowing a language by Claire Kramsch, a linguist at the University of California at Berkeley, which I found in Babel No More, by Michael Erard. The other definitions are somewhat similar to those in the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) in that they focus on linguistic competence. This one also considers pragmatic and cultural knowledge.

How deep you dive into a language and culture can depend on all sorts of factors, such as how much time you can spare, to what extent you can immerse yourself in the language and culture, whether you want to be accepted as a speaker rather than a learner, whether you want to blend in with the culture, or whether you just want to skim the surface and learn enough for your immediate needs. Maybe you see a language as a tool for communication; as a means to fit in; as a source of inspiration and/or information; as a challenge; or as as fascinating subject of study in its own right.

The languages and cultures I’ve dived most deeply into are Welsh and Irish, and to a lesser extent Scottish Gaelic, Manx, French and Mandarin Chinese. I have a more superficial knowledge of other languages and cultures.

At what stage would you say that you ‘know’ a language?

Here’s a recording in a mystery language.

Can you identify the language, and do you know where it’s spoken?

– filtre = filter = ffilter, hidl

– chargeur (de piles) = (battery) charger = gwefrwr (batri)

– le public = audience (cinema, theatre) = cynulleidfa

– l’audience, les auditeurs = (radio) audience, listeners = gwrandawyr

– les téléspectateurs = (TV) audience = cynulleidfa (teledu)

– le spectateur = member of the audience, spectator, onlooker

– l’icône (f) = icon = eicon

– l’éditeur (m) = publisher (company) = cyhoeddwr

– la maison d’édition = publishing house = cwmni cyhoeddi

– le nombril = navel = botwm bol, bogail

– le nombrilisme = navel-gazing, omphaloskepsis = bogailsyllu

– il pense qu’il est le nombril du monde = he thinks the world revolves around him – (dw i ddim yn siŵr sut i ddweud hyn yn Gymraeg)

I’ve been given free access to the online courses offered by Online Trainers to give them a try, and have one course to give away.

The languages available are English, French, Spanish, Italian, German and Dutch.

If you’re interested, just drop me an email at feedback[at]omniglot[dot]com and I’ll send you an access code that gives you three months’ free access to a course of your choice.

[addendum] This course has now been claimed. If I’m given any other free courses, I’ll let you know.

Omphaloskepsis /ˈɒmfələʊˈskɛpsɪs/ is an interesting word I came across today that refers to the practice of contemplating one’s navel as an aid to meditation. It comes from the Ancient Greek ὀμϕαλός (omphalos – navel) and σκέψις (skepsis -inquiry).

Apparently omphaloskepsis is used in yoga and sometimes in the Eastern Orthodox Church and it helps in the contemplation of the basic principles of the cosmos and of human nature, and naval is consider by some to be a ‘powerful chakra’.

Omphaloskepsis is also another word for contemplating one’s navel or navel-gazing, i.e. being self-absorbed.

The French equivalent of omphaloskepsis is nombrilisme, from nombril (navel) plus -isme (-ism), and the Welsh equivalent is bogailsyllu, from bogail (navel) and syllu (to gaze, look). A French idiom the revolves around the navel is penser qu’on est le nombril du monde (‘to think that one is the navel of the world’) or to think the world revolves around you. Are there similar phrases in other languages?

On another topic, have you ever heard or used the phrase “who’s she, the cat’s mother?”.

It is, or was, used to point out that referring to a woman in the third person in her presence is/was considered rude by some. It apparently was first noted in the OED in the late 19th century.

According to an article I came across yesterday music might be what enables us to acquire language, and spoken language could be thought of as a special type of music.

When acquiring language babies first hear speech as “an intentional and often repetitive vocal performance” and they learn to hear and mimic its emotional and musical components, such as rhythm and pitch, before they start to learn and focus on meaning. Being able to distinguish the different sounds of speech seems to be an essential first step for the acquisition of language. Newborn babies are able to distinguish phonemes of any language they hear, but gradually focus on the language(s) they hear most often.

The researchers also found connections between how the brain processes consonants and how it recognize the timbre of different instruments – both processes that require rapid processing.

These findings lend support to the idea that singing came before speech, as discussed in The Singing Neanderthals: The Origins of Music, Language, Mind and Body by Steven Mithen.

I find that it helps to spend time listening to a language to tune your ears to its sounds, and to mimic those sounds, even though you don’t understand what they mean at first – a bit like a baby. If you spend plenty of time listening to a language, when you learn words and phrases it’s easier because they already sound familiar. I probably heard hundreds of hours of Taiwanese while I was in Taiwan, for example, so it sounds familiar, even though I don’t understand much. If I decided to learn more of it, I would find it easier than a language I haven’t heard so much.

Some would call this passive listening, but it isn’t passive – your brain is busily working away trying to make sense of all these strange sounds you’re filling it with and looking for patterns. You can’t learn a language simply by listening – conversational interactions with others are also needed – but I think listening is an important part of the learning process.