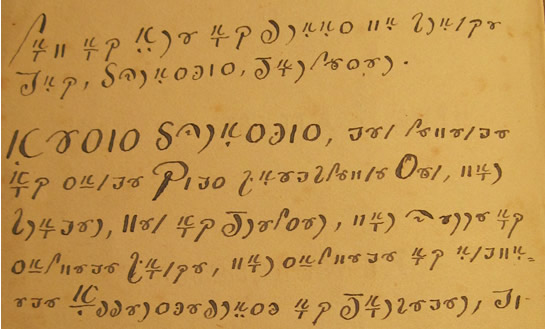

This image was sent in by a visitor to Omniglot who would like to know if anybody knows what writing system and language it’s in.

The text appears within a Danish hymn book published in 1879.

It looks a bit like cursive Hebrew to me, though appears to be written from left to right.

[Update] Here’s the full text:

Yes it is cursive hebrew I can say… i already recognized Aleph, Ayin, Feth (or Qof) with some diacretics as well.

But, if it is in a Danish book, then we might have also the possibility of Danish written in hebrew letters (like Yiddish?)?

@TJ: I believe your theory is spot-on! Take, for instance, the sequence of 9 characters on line 5, starting (left-to-right!) with what looks like a T surmounted by IC – which I imagine to be an aleph pronounced as “o”, as in Yiddish. The sequence could be: O K [qoph] F [pe raphe] R [resh] E [ayin, as in Yiddish] L [lamed] S [samech] E R = OK FRELSER? As I know VERY little Danish, I cannot vouch for this, but it certainly does look Danish…

Next comes a comma, then a double-waw (V?) starting the word VOR?

The large characters starting the third line I interpret as IESUS CHRISTUS, including:

aleph with underdot = I

s-shaped character = C

dotted arch = H

dotted thet = T

There are probably characters for æåø lurking somewhere…

If Kyrmse’s transliteration is correct then it definitely is Danish.

Frelser = saviour

vor = our

ok doesn’t mean anything, could it be og (=and)?

I read it thus:

Lov og ære og priis vi bringe

Dig, Christus forløser.

Iesus Christus, den levende

og sande Guds kiødblevne Søn, vor

broder, ven og Frelser, vor herre og

salvede konge, vor salvede og indvi-

ede ypperstepræst og forbeder, di

Unfortunately I don’t know any Danish, so I can’t translate it or check for errors very well.

David I agree with you, except that I think the last word is du and not di.

Here is my translation:

Praise and honour and praise we bring you, Christ, redeemer.

Jesus Christ, the incarnated son of the living and true God, our brother, friend and saviour, our lord and anointed king, our anointed and consecrated high priest and intercessor, you

It looks like the text is supposed to continue.

The spelling is slightly archaic and fits well with what I would expect from a text from 1879.

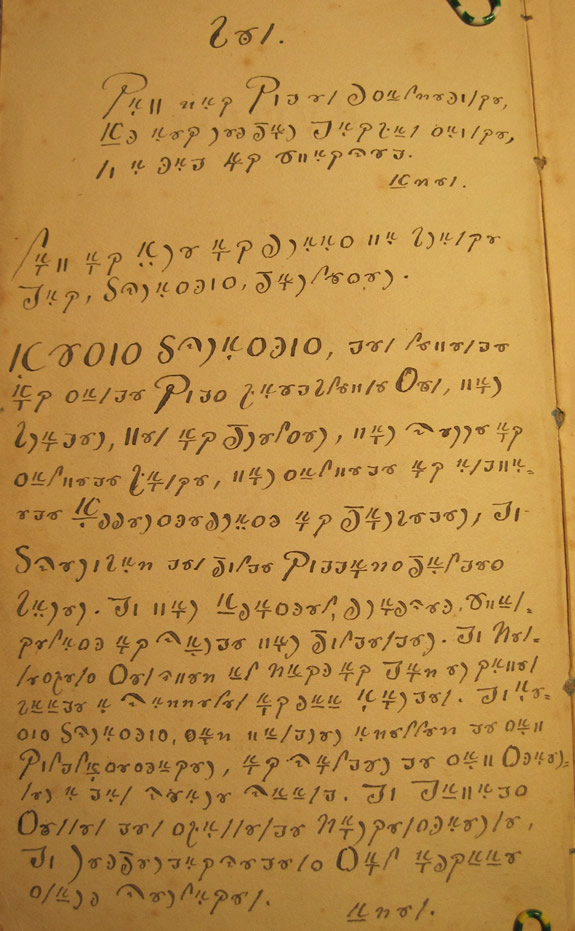

My transcription of the new material:

Bøn

Giv mig Gud en Psalmetunge

At ieg ret for Dig ban siung,

Nu i tid og evighed.

Amen.

[Then as before]:

Lov og Ære og Priis vi bringe

Dig, Christus forløser.

IESUS CHRISTUS, den levende

og sande Guds kiødblevne Søn, vor

broder, ven og Frelser, vor herre og

salvede Konge, vor salvede og indvi-

ede Ypperstepræst og Forbeder, du

[and then the new material]

Cherubim den fulde Guddoms Fyldes

bærer. Du vor Apostel, Prophet, Evan-

gelist og Hyrde vor Fuldelder. Du Men-

neskens Søn hvem al magt og Dom er given

baade i Himmelen og paa i arden. Du Ie-

sus Christus, som vandrer i mellem de syv

Guldlysestager, og holder de syv Stier-

ner, i din Høire Haand. Du Davids

Sønnen den skinnende Morgenstierne,

Du Retferdighedens Sol opgaae

snartherligen.

There are probably a few mistakes in the above, I didn’t doublecheck all that carefully.

Amen.

Again I agree with David.

I only have a couple of corrections.

The second line should probably be:

“At ieg ret for Dig kan siunge,”

And the in line “baade i Himmelen og paa i arden.” the last part should probably be ‘paa iorden’ (on earth)

A translation will follow later, when I have time.

Okay, here is my attempt at a full translation. I’m not used to working with this kind of vocabulary in English, so I’m sure there is lots of room for improvement.

———-

Prayer

Give me, God, a tongue of psalm,

So that I can rightly sing for You,

Now in time and eternity.

Amen.

Praise and honour and glory we bring You, Christ, redeemer.

Jesus Christ, the incarnated son of the living and true God,

our brother, friend and saviour, our lord and anointed king,

our anointed and consecrated high priest and intercessor,

You cherubim the carrier of the full form of God.

You our apostle, prophet, evangelist and shepherd our perfecter.

You son of man whom all power and judgement has been given on Earth as well as in Heaven.

You Jesus Christ, who walk among the seven golden lampstands and hold the seven stars in your right hand.

You the son of David, the shining morning star.

You sun of justice, rise soon in glory.

Amen.

———-

The first part seems to be inspired by the well know Danish psalm ‘Giv mig, Gud, en salmetunge’ by N.F.S. Grundtvig.

The last four lines are clearly a reference to the Book of Revelation.

Wow. Reminds me of the Afghan war rug solution a few months back. Give us a puzzle and sometimes we just swarm in, exchange, and… POW!

So now I wonder if this was just an individual cipher alphabet, or something used by some specific (small) community? Does the person who submitted this have any information about the background of this document?

Great. I think the issue is resolved now.

The thing that sounds weird to me here is that, if the text is of a Christian nature, then why it was written in Hebrew?

As I read the text, it is written by someone used to write in yiddish. Since the text appears in a Danish hymn-book the only explanation is, that it was written by a jewish convert. It looks as if his/her Danish is broken, he does’nt distinguish properly between ‘g’ and ‘k’, a characteristic of someone with yiddish as first language.

Morten Thing

Hi everybody,

As submitter of this mysterious text I first of all want to thank you VERY MUCH for solving this problem! I never imagined that this would happen so fast…

Now, as to the provenance of the text. A few weeks ago I bought the following hymn book from a bookseller in Aarhus, Denmark: Fleischer, A.F.H. (Udg.) – Hymner til Brug i Kirken og ved Huusandagten (1879)

Now, this is the (first published) hymnbook in Danish of a small religious group called the Catholic Apostolic Church (short: CAC). See the entries on Wikipedia: here and here. The German page mentions that this church had 59 congregations in Denmark around 1900. The main congregation was on the Gyldenløvesgade in Kopenhagen. A picture can be seen at the bottom of http://www.meng-soerensen.dk/Nostalgi/Katolskap.htm .

One of the distinctive features of the CAC was its elaborate structure of the various ministries. A fully equipped local congregation was lead by an Angel (= Bishop), together with a fourfold priestly ministry of Elder, Prophet, Pastor. This was the local ‘mirror’ of the fourfold ministry of Apostle, Prophet, Evangelist and Pastor which had the oversight over a so-called ‘tribe’ (see the English entry on Wikipedia for an explanantion of the tribes). This fourfold ministry is mentioned in the mystery text as well.

Regarding the compiler/editor of the hymnbook, Mr Fleischer, see:

http://da.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adolf_Fleischer. He also was a minister in the CAC.

The hymn book also has a handwritten name inscribed in it: A.C. Nielsen. Meanwhile I have discovered that he has been the Angel of the Catholic Apostolic congregation in Aarhus at the end of the 19th century. Here’s a photo of the church building (Frederiks Allé 37). I think the building still exists, though the Catholic Apostolic Church now is almost fully extinct (see the Wikipedia pages for the reasons of its demise).

The cursive Hebrew was written with a different pencil than the name of A.C. Nielsen. However, I am convinced that the person who wrote the Hebrew text was a member or minister of the CAC, because of the reference to the fourfold ministry.

To answer Christopher’s above question: No, I don’t think that this concealed way of writing was specific for the CAC or its ministers. But why someone would transcribe a prayer from Danish into cursive Hebrew?? I really don’t know.

Well, thanks again for your combined efforts. Without you I would ever have solved this puzzle!

Kind regards,

Edwin

I think that the writer of this piece probably acquired his knowledge of written Hebrew script from someone else who knew Yiddish, or from Yiddish books or letters which had fallen into his hands; but I do not think he was himself of Jewish origin or otherwise conversant with Yiddish. I base this on (a) the presence of obvious Yiddish values for some of the letters used, but (b) the very odd shapes some of the letters take, as if written by somebody not fully familiar with the script. The writer was also inventive enough to create entirely new letters in some cases (Y, Æ, Ø) — unless these were already in use among Danish Jews, which I suppose is possible. I would characterize this writing as a cipher using Hebrew letters, rather than an actual adaptation of the Hebrew alphabet to writing Danish.

These are the values he used, in Danish alphabet order:

A: Alef with patach. This is a Yiddish usage.

B: Beth, but a very curiously lax and elongated one.

C: Gimel? but again very oddly shaped; almost a mirror-image of Beth, and similar in shape to an S. Conceivably this shape is really the writer’s attempt at a zayin, or even a tsade.

D: Dalet, but again bizarrely shaped, rather like a script J

E: Ayin. This is a Yiddish usage.

F: Pe with a horizontal stroke on top. Yiddish.

G: Qoph. Not Yiddish, where qoph has the value /k/.

H: He.

I/J: Aleph with chireq. This is not Yiddish, which would have used a yod. Yod does not appear in this specimen.

K: Gimel, with a dagesh on the right side, and written lower in the line than C.

L: Lamed, but again written strangely, without the expected curl at the bottom.

M: Mem, again written strangely, in two separate strokes.

N: Nun, written as a single slash / .

O: Aleph with qamets. This is Yiddish.

P: Pe.

R: Resh, but again written laxly, resembling a right parenthesis – )

S: Samekh. In some cases the letter has a dimple in the bottom or top, which I think is not meant to be distinctive, but shows that the writer wrote the letter as two joined semicircles, rather than simply making a circle with his pen.

T: Tet, I _guess_ — but really this letter looks like nothing so much as a kaph with a dagesh in it.

U: Vav. Yiddish.

V: Doubled vav. Yiddish (where it is probably inspired by German W)

Y: Aleph with patach and then a chireq below the patach. An invented letter.

Æ: Aleph with two dots underneath. An invented letter. (But compare the Yiddish usage of a double yod for ai or ei.)

Ø: Ayin with a dagesh in it. An invented letter.

Å: Two A’s in succession, as in the older orthography.

The letters Q, X, Z do not appear.

I should add that, if the author had been a Jewish convert to this sect, or had been following any established system of Hebrew-letter transliteration, he would have (a) automatically used final letters where appropriate (like final nun or final mem) and (b) he would have written from right to left!

I have seen attempts at writing using Arabic letters that were similar: with unjoined letters, written left to right, as if the writer had simply consulted an alphabet table and assumed that all other conventions of the Roman alphabet applied.

In my opinion, in such handwritten samples, we cannot rely heavily on an analysis dependant on the shapes of the letters or the script, as it is a matter of fact that the personal style of calligraphy changes from one individual to another.

I’m not so familiar with Yiddish, but I think I saw some samples where final letters were not used for Nuns or Mems and the others. Yet, I do recall Yiddish was written from right to left, and maybe this is the only point that opposes the idea of a convert Jew (from a Yiddish origin).

I’m not a Danish speaker myself but I take a note that there sounds to be some general ambiguity in the letters ‘g’ and ‘k’ used by the writer of the text. This point could have several meanings though, either as Morten said about some non-Dane person writing in Danish and could not differentiate the sounds correctly, or it could also mean, maybe, that the Danish of that time was in fact written that way. I think we read many times that Norwegian and Danish are always developing languages with many variants, and I take also some examples of German where “ich” is pronounced like the Dutch “ik” (but written “ich” still), specifically in areas closer to the Dutch side.